The Complainant is Trade Me Limited of Wellington, New Zealand represented by its General Counsel, Christine Turner.

The Respondent is Vertical Axis, Inc of Christ Church, Barbados, represented by Ari Goldberger Esq. of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, United States of America.

The disputed domain name <trademe.com> is registered with Nameview Inc.

A Complaint was filed with the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (the “Center”) on January 23, 2009 naming as respondent “TRADEME.COM”, c/o WhoIs Identity Shield of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. On that day the Center transmitted by email to Nameview Inc a request for registrar verification in connection with the disputed domain name. On January 27, 2009 Nameview Inc transmitted by email to the Center its verification response noting that the registrant of the disputed domain name was Vertical Axis Inc. On January 30, 2009 the Center asked the Complainant to file an amended complaint adding Vertical Axis Inc as respondent, and this was duly done on February 10, 2009. Any subsequent references in this decision to the Complaint are to be taken to be references to the Amended Complaint and references to the Respondent are to be taken to be references to Vertical Axis Inc unless otherwise expressly noted. The Center verified that the Complaint satisfied the formal requirements of the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Policy” or “UDRP”), the Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Rules”), and the WIPO Supplemental Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Supplemental Rules”).

In accordance with the Rules, paragraphs 2(a) and 4(a), the Center formally notified the Respondent of the Complaint, and the proceedings commenced on February 10, 2009. In accordance with the Rules, paragraph 5(a), the due date for Response was March 2, 2009. The Response was filed with the Center by email on March 2, 2009 with a fax copy filed on March 3 and a hard copy on March 9, 2009. The Complainant lodged a Supplementary filing on March 6, 2009 purporting to respond to matters in the Response that it says it could not have anticipated. For the reasons given in section 6 below, the Panel has taken into consideration the Supplementary filing.

The Center appointed Philip N. Argy, Ian Barker and David Sorkin as panelists in this matter on March 24, 2009. The Panel finds that it was properly constituted. Each member of the Panel has submitted the Statement of Acceptance and Declaration of Impartiality and Independence, as required by the Center to ensure compliance with the Rules, paragraph 7.

The Complainant is the owner of a number of New Zealand registered trademarks for stylized forms of TRADE ME, for five variants of the phrase “Trademe where kiwis buy and sell” (with the variants comprising upper and lower case renditions and the insertion of a space between “trade” and “me”), for a stylized form of “trademe.co.nz where Kiwis Buy and Sell Online”, for two further variants of the latter mark in which “Online” is not capitalized and for a stylized form of “trade metrademe”. Its earliest application for a trademark was filed on July 24, 2003. It also holds a trade mark registration in Australia for the two words TRADE ME and for a miniature stylized version of “trademe where Kiwis buy and sell online”.

It operates an online auction business at “www.trademe.co.nz” and is the registrant of the domain name <trademe.co.nz>.

The Respondent is in the business of registering domain names for use with paid search advertising. The disputed domain name <trademe.com> was originally registered in 1999 by a third party but when that registration lapsed the domain name was deleted. It was subsequently registered by the Respondent on July 18, 2001. The disputed domain name resolves to a website at “www.trademe.com” (the “<trademe.com> website”).

The Respondent is the registrant of more than 10,000 domain names amongst which are included <trade.com>, <tradeyou.com>, <tradeit.com>, <cartradeonline.com>, <tradecon.com> and <trademore.com>.

The Complainant asserts that the disputed domain is identical to the Complainant's registered and common law TRADE ME marks, that the Respondent lacks any rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name, and that the disputed domain name “is [sic] registered and being used in bad faith”.

According to the Complainant, in addition to its registered trademarks, it has acquired common law trade mark rights to TRADE ME because the term “Me” and “variations thereof” and the “Trade Me Domain Name” have become distinctive identifiers associated with the Complainant and its services. In support of its contention it annexes to the Complaint copies of numerous newspaper articles, consumer surveys and statistics. It also argues that its common law rights are substantiated by the top ranking achieved in a Google search for its domain name and for “trade me” and variants, and that those terms have also acquired secondary meaning as its brand name in which it has considerable goodwill. In support of the latter contention it annexes evidence of a large volume of sales made via its platform, its media recognition, its profitability, the results of a survey in which a sample of 500 New Zealanders regarded the Complainant as more trustworthy than banks, supermarkets, department stores, the legal profession and the police, and the fact that “Trade Me” is not a phrase that people ordinarily associate with online auctions, real estate and other classifieds.

The bases on which the Complainant contends that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name are:

(a) First, there is no evidence of the Respondent's use of or demonstrable preparations to use the disputed domain name or a name corresponding to the disputed domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. In particular, the Complainant notes that although the <trademe.com> website appears to offer services similar to those provided by the Complainant, on a closer analysis it is being used purely to generate revenue from advertising based on the goodwill that the Complainant has established in TRADE ME as a brand for advertising online auctions, cars, real estate, classifieds and related services;

(b) Secondly, there is no evidence that the Respondent has been commonly known by the disputed domain name and the Respondent has never registered a trade mark with the words “trade” or “me”;

(c) Thirdly, the Respondent is not making a legitimate non-commercial or fair use of the disputed domain name. It is attempting to achieve commercial gain misleadingly by diverting consumers who mistakenly type in the Trade Me Domain Name and are diverted to the Respondent's “mock auction site”. The Complainant further argues that “the amateur design of the Respondent's website tarnishes the Complainant's trademarks and name”. It seeks to distinguish the present case from other cases where the generic value of words were used “without intending to take advantage of complainant's rights in that word”, such as Allocation Network GmbH v. Steve Gregory, WIPO Case No. D2000-0016, Porto Chico Stores Inc. v. Otavio Zambon, WIPO Case No. D2000-1270, Asphalt Research Technology, Inc. v. National Press & Publishing Inc., WIPO Case No. D2000-1005 and Gorstew Limited v. Worldwidewebsales.com, WIPO Case No. D2002-0744

(d) Fourthly, the status and fame of the Complainant's trademarks and the fact that the words “trade” and “me” and the phrase “trade me” are not what one would ordinarily associate with online auctions or with real estate, motors and other classifieds, means that the <trademe.com> website is designed to gain commercially from the goodwill that the Complainant has established in TRADE ME as a brand for online auction of goods and for classified listings; and

(e) Based on cases such as Croatia Airlines v. Modern Empire Internet Ltd., WIPO Case No. D2003-0455 and Belupo d.d. v. WACHEM d.o.o., WIPO Case No. D2004-0110, that the foregoing four points establish a prima facie case so that the Respondent's failure to demonstrate rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name means that the Complainant must succeed under paragraph 4(a)(ii) of the Policy.

In support of its contention that the disputed domain name “is” registered and is being used in bad faith, the Complainant submits:

(a) Given the number of trade marks (both registered and common law) held by the Complainant, and its wide reputation in the name TRADE ME, it is not possible to conceive of a circumstance in which the Respondent could have legitimately registered the disputed domain name and been unaware of the illegitimacy of its registration at the time of registration. The Complainant asserts that the present case is comparable with Telstra Corporation Limited v. Telsra com/Telecomunicaciones Serafin Rodriguez y Asociados, WIPO Case No. D2003-0247;

(b) By using the disputed domain name, the Respondent is “intentionally attempting to attract for commercial gain, Internet users to the disputed domain name, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant's mark as to the source of the Respondent's website”;

(c) The phrase “Trade Me” is not one that people would ordinarily associate with online auctions, or with real estate, cars, pets and other classifieds unless they were aware of the Complainant's well known brand. It is clear, so the Complainant contends, that by creating the <trademe.com> website the site is designed to make commercial gain from the goodwill that the Complainant has established in “Trade Me” as a brand for those services.

(d) As in the Telstra case, it is relevant that the Complainant's mark has a strong reputation and is widely known.

The Respondent maintains that it is in the business of registering domain names incorporating common words, phrases and expressions for use with paid search advertising. According to the Respondent, it registered the disputed domain name on July 18, 2001, because it incorporates two words in the English language. By a statutory declaration of its Domain Manager, Mr. Chad Park, made in British Columbia, Canada, the Respondent states that as at July 18, 2001 it believed the disputed domain name “was not subject to third party trademark rights”.

Mr. Park further states that:

(a) the Respondent did not operate in Australia or New Zealand in July 2001 or at any time;

(b) the Respondent did not register the disputed domain name with the Complainant's trademark in mind and had no knowledge of Complainant, its web site, its business name or trademark when it registered the disputed domain name;

(c) the Respondent did not register the disputed domain name with the intent to sell it to the Complainant, to disrupt Complainant's business, or to confuse consumers seeking to find Complainant's web site;

(d) the Respondent did not register the disputed domain name to prevent the Complainant from owning a domain name incorporating its trademark;

(e) the Respondent has registered more than 16 other domain names containing the word “trade”;

(f) the Respondent hosts the <trademe.com> website with HitFarm.com, a domain name parking service, which displays pay-per-click advertising links on hosted domain names powered by a feed from Yahoo!;

(g) Yahoo and HitFarm's automated technology generate links based on contextual meaning of the terms and words contained in the domain name, which in this case is primarily “trade”;

(h) The Respondent did not select any links on the <trademe.com> website with the intent to profit from Complainant's trademark; and

(i) The links displayed on the <trademe.com> website are automated sponsored search results provided by the domain name parking service HitFarm through a feed from Yahoo! The technology parses the domain name into its relevant parts, “trade” and “me” and then returns what are suggested searches related to the contextual meaning of the terms. In addition, Yahoo! returns results based on what advertisers are bidding on. There was no conscious effort directly or indirectly on the part of the Respondent to place auction or any ads based on knowledge of the Complainant's mark or business.

The Respondent further submits that “trade me” is descriptive even if grammatically unconventional. It connotes “something dealing with the buying, selling or exchange of goods or services”. It is no less a legitimate combination of English words than YouTube and iPhone. The Respondent claims that its choice of domain names is dictated by the attributes that they are easy to remember and easy to spell words which are also descriptive.

The Respondent argues that the legitimacy of its interest in the disputed domain is bolstered by its use to display pay-per-click links and it maintains that argument even in the face of “a few” automated and “unintended” links on its website which promote services similar to those covered by Complainant's trademark. The Respondent asks the Panel to take into consideration that the Respondent owns more than 10,000 domain names and that, whilst it uses discretion in registering domain names to avoid trademark issues, “it is virtually impossible to be aware of every trademark in every country in the world that is similar to a descriptive domain name it has registered and, at the same time, be aware of every advertising link appearing on every associated web page at any given time”.

The Complainant operates in New Zealand and restricts its membership to New Zealanders and Australians. It had no interest in promoting its business to outsiders and the Respondent says it was obviously one of those outsiders to whom the Complainant did not get its message. It says further that it is plain that the Complainant, at least when it commenced its business, would not expend marketing dollars to promote its brand outside of New Zealand.

The Respondent notes the Complainant's evidence that as at July 12, 2001 it had only 47,000 members compared to its current membership of 2.15 million members, which it contrasts with a current population of New Zealand of 4.2 million. The Respondent contends that the Complainant has not discharged its burden of showing that it had common law trademark rights as at July 18, 2001 and says that, absent a registration, such rights are a necessary pre-requisite for the Complainant to have any standing to file the Complaint. In addition to four National Arbitration Forum cases, it cites in support of this proposition John Ode d/ba ODE and ODE – Optimum Digital Enterprises v. Internship Limited, WIPO Case No. D2001-0074.

In order to establish common law trademark rights to “trade me”, the Respondent says that the Complainant must establish, but has failed to establish, a secondary meaning by evidence that consumers identify the term “trade me” exclusively, or almost exclusively, with its products: Amsec Enterprises L.C., v. Sharon McCall, WIPO Case No. D2001-0083 and Advanced Relational Technology, Inc. v. Domain Deluxe, WIPO Case No. D2003-0567. Failure to establish such secondary meaning is said to be fatal to the Complainant's case: Advanced News Service, Inc. v. Vertical Axis Inc/Religionnewsservice.com, WIPO Case No. D2008-1475.

The Respondent argues strongly that it has a legitimate interest “in” the disputed domain name. It says so much flows from the descriptive nature of the words comprising the domain name and the fact that it was not registered with a trademark in mind: Metro Sportswear Limited (trading as Canada Goose) v. Vertical Axis Inc. and Canadagoose.com c/o Whois Identity Shield, WIPO Case No. D2008-0754 and Bacchus Gate Corporation d/b/a International Wine Accessories v. CKV and Port Media, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2008-0321.

There a number of recent cases in which the legitimacy of the Respondent's interest in various domain names has been assessed in the context of its use of them for pay-per-click sites. The most recent case is Alexis C Le Hara v. Vertical Axis Inc c/o Domain Administrator, NAF Claim No 1225832 which found that Respondent's “business has been held legitimate on more than one occasion”, citing for that proposition Super Supplements, Inc. v. Vertical Axis, Inc. WIPO Case No. D2008-0244, Jet Marques v. Vertical Axis, Inc. WIPO Case No. D2006-0250 and Nursefinders, Inc. v. Vertical Axis, Inc / NURSEFINDER.COM c/o Whois Identity shield, WIPO Case No. D2007-0417.

The Respondent answers the Complainant's references to auction-related links on its current website by saying they were unintended by the Respondent and do not make the Respondent's interest illegitimate. The Respondent says that it did not select the links but adds that they were auto-generated by HitFarm and Yahoo!. It cites a three member panel decision in Mariah Media Inc v. First Place Internet Inc., WIPO Case No. D2006-1275, for the proposition that “the appearance of links created by a third party domain monetization service does not constitute bad faith on the part of the domain owner”.

In relation to bad faith registration and use the Respondent makes the following further submissions in addition to its foundation argument that the Complainant has failed to discharge its evidentiary burden given its failure to apply for a trade mark until two years after the disputed domain name was registered by the Respondent:

a) The expiration of a domain name is a signal that any trademark claim to the domain name was abandoned and that the domain name could be registered in good faith: Corbis Corporation v. Zest, NAF Claim No 98441;

b) The cases in which the Respondent has been a respondent have uniformly considered as legitimate the Respondent's practice of registering deleted common word domain names where there is an absence of bad faith registration or use;

c) Absent proof of intent to profit from the Complainant's mark, bad faith registration cannot be established; and

d) Even if the use of auction-related links are found to be a bad faith use, which is denied, the Complaint must fail in the absence of evidence of bad faith registration.

The Complainant seeks to have its unsolicited supplementary submission accepted on the following grounds:

(A) The Respondent made the following material misrepresentations in the Response:

i. The Respondent's incorrect assertion that the Complainant's website was a “part-time venture between 1999 and July 18, 2001”;

ii. The Respondent's incorrect assertion that the Complainant did not have a reputation outside New Zealand as at July 18, 2001; and

iii. The Respondent's incorrect assertion that the Complainant's “TRADE ME” trademark was descriptive only and not distinctive of the Complainant as at July 18, 2001;

The misrepresentations are said to be relevant because a previous panel expressed the view that a divergence of views between parties as to basic facts is reason to permit a supplementary filing: Viacom International and MTV Networks Europe v. Rattan Singh Mahon, WIPO Case No. D2000-1440.

The Complainant then asserts, supported by a statutory declaration of its general counsel, that:

i. In July 2001 the Complainant recorded 9,592,524 page impressions; and

ii. If a Google or Yahoo search for “trade me” had been carried out on July 18, 2001, the Complainant believes its website would have been the top ranking result returned from which it is said to follow that the Respondent would have had at least constructive knowledge of the Complainant's “www.trademe.co.nz” website and trademark as at July 18, 2001.

The Complainant then contends that the trademark TRADE ME is not a descriptive term in its ordinary and usual use. Traders and members of the public do not trade themselves, which is what the Complainant says is conveyed by “trade me”. It goes on to contend that the words do not have any descriptive meaning or allusion in respect of a click through portal such as the <trademe.com> website and that “trade me” has no descriptive meaning in respect of an auction site where vendors sell goods or services.

(B) The Respondent's registrant details were blocked by a “privacy shield” with the Complainant not being able to know or ascertain the identity of the Respondent at the time of filing the original Complaint. Further, insufficient time was afforded for amendment of the Complaint once the identity and registration details of the Respondent had been supplied by the WIPO case manager. This is said to be relevant because “new evidence has come to and evidencing knowledge of the Complaint's website and bad faith on the part of the Respondent, namely, use on the <trademe.com> website of certain of the Complainant's key services and trademarks, namely, “Trade Me New Zealand”, “Find Someone”, “Old Friends” and the use of geographical indicators such as “Wellington”, “New Zealanders” and “Zealands”. The Complainant also relies on the fact that the Respondent admits to having registered over 10,000 domain names.

Where the Complainant could not reasonably have addressed issues in its initial complaint a supplementary filing has been accepted in Delikomat Betriebsverpflegung Gesellschaft MbH v. Alexander Lehner, WIPO Case No. D2001-1447.

The use of a privacy shield prevented the Complainant from finding out full details of the Respondent and its previous activities and the inability of the Complainant to obtain information and to make enquiries denied it a fair opportunity to present its case as required by paragraph 10(b) of the Rules.

The Complainant refutes the Respondent's legal submissions as to the bona fides of the auction-related links that appear on the <trademe.com> website and submits that such links do not legitimize the Respondent's use of the disputed domain name.

The Complainant cites two earlier cases in support of the proposition that a domain name registered for its descriptive value will only constitute a legitimate interest for the purposes of paragraph 4(c) of the Policy where the domain name has not been registered for its value as a trade mark and only if it has been used solely in connection with its descriptive meaning and without knowledge of “the Complainant's” trademarks: Ustream.tv Inc v. Vertical Axis, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2008-0598 and Asian World of Martial Arts Inc. v. Texas International Property Associates, WIPO Case No. D2007-1415.

The subsequently discovered evidence is said to cast “real doubt on the claimed bona fides of the Respondent's claimed legitimate interest in the domain name” and the Complainant again cites the use on the <trademe.com> website after about 2005 of many of the key words used on the Complainant's site.

The Complainant asserts that “the Respondent's use of robot.txt or similar service” prevented the Complainant from reviewing via the Wayback Machine “www.archive.org” versions of the <trademe.com> website as they existed immediately after July 18, 2001, the earliest version said to be viewable by the Complainant being September 2001.

The Complainant also contends that the use of automated processes by the Respondent to “register websites” and to generate pay-per-click automated links on its website does not legitimize the Respondent's conduct.

The Complainant then proceeds to rely on the same facts to support its unsolicited supplementary contentions in relation to bad faith registration and use, as follows:

i) paragraph 2 of the Policy imposes a positive obligation on registrants to ensure that their registration of a domain name does not “infringe upon or otherwise violate the rights of any third party”;

ii) any Google or Yahoo search of “trade me” as at July 18, 2001 “would clearly have listed the Complainant as no 1 in the results list” because there is no evidence of any other trader at the time using “trade me”;

iii) the fact that versions of the <trademe.com> website after 2005 include links to the Complainant and its website show clear recognition of the existence and reputation of the Complainant. The Complainant “believes that” these links would also be on the earlier versions of the Respondent's website thus demonstrating the requite knowledge of the Complainant and therefore bad faith at the time of registration of the disputed domain name;

iv) the Respondent's reliance on later-registered domain names such as <tradeit.com> does not justify its 2001 registration of “trade me”;

v) the confusion evidence annexed to the Complaint establishes the factual basis for paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy to be invoked;

vi) where a respondent registers large numbers of domain names and where there is targeted advertising through automated click through links then a reasonable good faith effort to avoid registering domain names that are identical or confusingly similar to “others” must be observed, which the Respondent here has not demonstrated: Balgow Finance S.A., Fortuna Comercio e Franquias Ltda. v. Name Administration Inc. (BVI), WIPO Case No. D2008-1216; Grundfos A/S v. Texas International Property Associates, WIPO Case No. D2007-1448.

vii) the Complainant had acquired an extensive reputation beyond New Zealand as evidenced by the large number of page impressions it had, and its Red Sheriff (now Neilsen NetRatings or Neilsen Online) statistics support that submission.

viii) the use of a privacy shield supports a finding of registration and use in bad faith: Sermo Inc v. CatalystMD, LLC, WIPO Case No. D2008-0647. The Respondent has admitted it is a “serial registrant”, it uses a privacy shield to mask its details and that this defeats the UDRP's objective of curbing abusive registrations: Fifth Third Bancorp v. Secure WhoIs Information Service, WIPO Case No. D2006-0696.

ix) the Respondent has “a reputation” for registering domain names that are confusingly similar to trademarks in which other owners have rights: TT-Line Company Pty LTD. v. Vertical Axis, Inc, WIPO Case No. D2007-1742.

(C) The Panel has not yet convened.

The Complainant submits that a supplementary filing lodged before a panel is convened and in response to new material will not lead to any undue complication or delay: AutoNation Holding Corp. v. Rabea Alawneh, WIPO Case No. D2002-0058.

The Policy is addressed to resolving disputes concerning allegations of abusive domain name registration and use. Milwaukee Electric Tool Corporation v. Bay Verte Machinery, Inc. d/b/a The Power Tool Store, WIPO Case No. D2002-0774. Accordingly, the jurisdiction of this Panel is limited to providing a remedy in cases of “the abusive registration of domain names”, also known as “cybersquatting”. Weber-Stephen Products Co. v. Armitage Hardware, WIPO Case No. D2000-0187. See Report of the WIPO Internet Domain Name Process, paragraphs 169 and 170.

Paragraph 15(a) of the Rules provides that the Panel is to decide a complaint on the basis of statements and documents submitted and in accordance with the Policy, the Rules and any other rules or principles of law that the Panel deems applicable.

Paragraph 4(a) of the Policy requires that the Complainant prove each of the following three elements to obtain a decision that a domain name should be either cancelled or transferred:

(i) The domain name registered by the Respondent is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the Complainant has rights;

(ii) The Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests with respect to the domain name; and

(iii) The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

Cancellation or transfer of the domain name is the sole remedy provided to the Complainant under the Policy, as set forth in paragraph 4(i).

Paragraph 4(b) of the Policy sets forth four situations under which the registration and use of a domain name is deemed to be in bad faith, but does not limit a finding of bad faith to only these situations.

Paragraph 4(c) of the Policy in turn identifies three means through which a respondent may establish rights or legitimate interests in a domain name. Although the complainant bears the ultimate burden of establishing all three elements of paragraph 4(a) of the Policy, panels have recognized that this could result in the often impossible task of proving a negative, requiring information that is primarily if not exclusively within the knowledge of a respondent. Thus, the consensus view is that paragraph 4(c) shifts the practical burden to the respondent to come forward with evidence of a right or legitimate interest in the domain name, once the complainant has made a prima facie showing. See, e.g., Document Technologies, Inc. v. International Electronic Communications Inc., WIPO Case No. D2000-0270.

There is no provision in the Policy, the Rules or the Supplementary Rules for a Complainant to reply to a Response. This is to ensure that the UDRP regime provides a swift and cost effective administrative mechanism for removing abusive registrations, albeit at the cost of inhibiting a party's (and the panel's) ability to test evidence and the credibility of witnesses as would be possible in a normal adversarial legal proceeding. The Complainant nevertheless relies on paragraph 10(b) of the Rules which requires a Panel to afford each party a fair opportunity to present its case. For that reason previous panels have had little difficulty in receiving and considering supplementary submissions from a complainant where it was able to demonstrate the existence in a response of submissions it could not reasonably have anticipated.

This Panel would have had no hesitation in affording each party more time and the opportunity to make further submissions if we had thought this was necessary to enable a party to receive the benefit of paragraph 10(b) of the Rules. In this case we have come to the view that certain parts of the Complainant's Supplementary submission are entitled to consideration but those parts that repeat arguments already contained in the Complaint, or which deal with matters that ought to have been dealt with in the Complaint in anticipation, are not.

In our view a complainant must have an opportunity to rely on paragraph 4(b) of the Policy where it can adduce evidence to support the operation of any of those provisions. Plainly to be able to do that it needs to know the identity of the registrant of a disputed domain name. Where a privacy shield has been used to deny a complainant that opportunity, we would have no hesitation in allowing a supplementary filing to make those sorts of submissions once the identity of a registrant has been revealed. In this case we have therefore decided to consider the parts of the Complainant's supplementary filing which go to aspects of the Respondent's conduct or business that could not have been the subject of considered submissions between the discovery of the registrant's true identity, and the time allowed by the Center for the filing of an amended complaint which adds the true name of a respondent to that of the privacy shield whose details appear in the public WhoIs record.

In the present case the relatively unusual nature of the Respondent's business, in having as its selection mechanism for domain names the lapsing and deletion of domain names comprising dictionary words, could not have been anticipated by the Complainant. Nor could the fact that the Respondent is the registrant of over 10,000 other domain names, nor the fact that the Respondent has been the subject of a large number of other proceedings under the UDRP. We doubt that a commercial business with over 10,000 domain names requires the benefit of a privacy shield. Our view that such a practice inhibits and can be used to thwart the achievement of swift outcomes under the UDRP is another reason to exercise our discretion in favour of the Complainant by admitting the Supplementary Submission.

As we have indicated, however, a complainant should not take advantage of the opportunity presented by a supplementary submission to conduct a full reply to the response, tempting though that may be. A complainant who does not assiduously confine itself to the issues the legitimate subject of a supplementary submission risks also finding itself out of favour with most panelists.

The inquiry under the first element of the Policy is simply whether a trademark and the disputed domain name, when directly compared, are identical or confusingly similar. The contents of any website to which a disputed domain name resolves is not relevant to this ground of a complaint: Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v.xc2, WIPO Case No. D2006-0811 and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Traffic Yoon, WIPO Case No. D2006-0812. See also Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Richard MacLeod d/b/a For Sale, WIPO Case No. D2000-0662 and Magnum Piering, Inc. v. The Mudjackers and Garwood S. Wilson Sr., WIPO Case No. D2000-1525.

It is also accepted that, due to the technical idiosyncrasies of domain name syntax, the use of lower case characters, the omission of blank spaces between words, and the suffixing of a domain level signifier such as “.com” or “.co.nz”, may be ignored for the purposes of the comparison. In this case, a comparison between TRADEME and <trademe.com> reveals that the disputed domain name and the Complainant's mark are identical.

The Panel rejects the Respondent's submission that paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy requires that the time at which the Complainant must demonstrate that it “has rights” in a trademark to be the time of registration of the disputed domain name. This Panel is of the unanimous view that the present tense “has rights” in paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy requires a Complainant to demonstrate its rights in a trademark as at the date of filing its Complaint. It is true that the language of the Policy is directed at registrants, and that by force of their registration agreement (in this case paragraph 8 of the Respondent's agreement with Nameview) registrants are expected to give the warranty in paragraph 2 of the Policy as at the date of registration of their domain name. But the fact that the registration agreement contemplates that the Policy will be invoked “in the event such a dispute arises” seems to us to bolster rather than detract from the proposition that the only showing required of a Complainant under paragraph 4(a)(i) is a showing of rights contemporaneous with the commencement of the proceedings.

The Panel finds that the disputed domain name <trademe.com> is identical to the Complainant's TRADEME mark, in which the Complainant has demonstrated rights for the purposes of paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has satisfied comfortably the requirements of paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy.

The Panel agrees with the Complainant's submission that, once a complainant makes a prima facie showing under paragraph 4(a)(ii) of the Policy, in practical terms a respondent is obliged to come forward with evidence of rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name. Whether that be by way of evidence to support the operation of paragraph 4(c) or some independent basis is a matter for the respondent. The Panel has found that the disputed domain name is identical to the Complainant's mark. It is also uncontroverted that the Complainant has not authorized the Respondent to use its TRADEME mark or to register a domain name that corresponds to the mark. The Complainant contends that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name, which is identical to the Complainant's mark, and is using the domain name to generate click-through advertising revenues.

Fundamental to the argument run by the Complainant, and indeed by so many complainants, under paragraph 4(a)(ii) of the Policy, is the dual proposition that any right to use a disputed domain name that is identical to a trademark can only come from the trademark owning complainant, and that any legitimate interests in the disputed domain name can only derive from a relationship with the trademark-owning complainant. Where a disputed domain name comprises invented words and there is an identical trademark owned by a complainant at the time of registration of the disputed domain name, panels have consistently taken the view that the complainant has made a prima facie case under paragraph 4(a)(ii) of the Policy. However, given that under the Nice classification system there can be more than 40 identical trademarks in respect of non-overlapping areas of commerce, even such a prima facie showing can be relatively easily displaced if the complainant and the respondent are not operating in overlapping areas of commerce.

The fact that a trademark can (at present) only be reflected in one second level domain name for each generic top level domain (gTLD) such as .com, .net and .org (and only one third level domain name for each country code top level domain that uses gTLD analogs for its second level domains) often gives rise to conflict. The Policy is designed to deal with relatively simplistic examples of abusive registration. It does not provide for detailed in-person hearings nor for the nuances of the adversarial process, nor for the testing of credit of evidence and witnesses. Panels therefore are limited in their ability to make findings of credit except in cases where the evidence is persuasive in one direction on that kind of issue. In most cases the onus of proof being on the complainant, even at the “balance of probabilities” level, essentially gives a respondent the benefit of any doubt. Nevertheless, where a complainant makes out a prima facie case, then as a matter of forensic logic it will be found to have proven that element of the Policy if the respondent does not at least plausibly refute any of that prima facie case.

In this case, where the Complainant did not even apply for a trademark until two years after the Respondent registered the disputed domain name, there can be no prima facie case absent the Complainant's proof that the Respondent knew of its common law trademark rights as at July 18, 2001. Where the words comprising the alleged common law mark are ordinary English words, and the Complainant's business has been relatively restricted geographically, this is an onerous burden for a complainant to discharge. In this case the Complainant has adduced a good deal of reputational evidence that satisfies the Panel that it currently enjoys a very widespread reputation in New Zealand. What we have not been persuaded of is that as at July 18, 2001 the words “trade me” were so unmistakably associated with the Complainant by New Zealanders (let alone any more geographically distributed Internet users) that any use of them in relation to the trading of any goods or services would have lead to an assumption that the Complainant was the trade source, or that the Respondent must therefore have registered the disputed domain name with the Complainant's mark in particular in mind. The Respondent's assertion, that 47,000 members of the Complainant's service out of a population of about 4.5 million people is not sufficient to discharge this evidentiary burden, is compelling. However, rather than determine the case on such a fine point where other reasonable minds may differ, we think it appropriate to consider the balance of the parties' contentions.

Pursuant to paragraph 4(c) of the Policy, a respondent's rights to or legitimate interests in respect of a disputed domain name may be demonstrated by any of the following:

(i) before any notice to it of the dispute, the respondent's use of, or demonstrable preparations to use, the domain name or a name corresponding to the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services; or

(ii) the respondent has been commonly known by the domain name, even if it has acquired no trademark or service mark rights; or

(iii) the respondent is making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue.

Whilst paragraph 4(c) of the Policy provides a respondent with a basis on which its rights or legitimate interest in a disputed domain can be taken to have been established without more, there is no requirement for a respondent to address itself to that provision and likewise, even where there is no response, panels may invoke that provision if the evidence submitted by the complainant enables a panel to see that the requirements of that provision have been satisfied. Ordinarily, a complainant will attempt, in anticipation of a response, to deny any factual basis for that provision to operate. Although there is no express requirement for a complainant to address itself to that provision, the absence of any automatic right of reply to a response under the Policy makes it prudent for a complainant to address that provision in anticipation.

In this case the Complainant has attempted to negate in anticipation the operation of paragraph 4(c) of the Policy but the Respondent has argued forcefully that it is entitled to the benefit of the paragraph (as well as arguing its position independently of that paragraph). The Panel therefore needs to address the parties' arguments in a little detail.

The first question is whether the Respondent, prior to having notice of this dispute, had used or made preparations to use the disputed domain name. The Respondent has been the registrant of the disputed domain name for more than seven years before the Complainant took any action. Where, as here, the disputed domain name has been for virtually all of that time parked with HotFarm's monetization service, there is a threshold issue of whether that amounts to use or preparations to use the disputed domain name by the Respondent. Whilst the issue is not beyond argument, we think that a use by which the Respondent receives revenue can be use by the Respondent, even if the Respondent never as it were takes ‘possession' of its domain name and delegates to others the exercise of the rights attached to the domain name.

If parking its domain name with the monetization service operated by HotFarm is use by the Respondent, the next question is whether that use is “in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services”. That seems to us a more difficult question to answer. Whose bona fides are to be tested? Given the context in which paragraph 4(c) appears in the Policy and the purposes to which it is directed, it seems to us that it has to be the Respondent whose bona fides are to be tested. So although the Policy does not expressly require the offering of goods and services to be an offering of goods and services by the Respondent, that seems to us to be the most logical interpretation as well as the usual scenario in most cases.

Does the website to which a disputed domain name resolves have to be a website at which there is an offering of goods or services by or at least on behalf of a respondent? In our view the words “in connection with” accommodate a relatively loose nexus. In this case we have the Respondent's domain name being used to generate payments from HotFarm who the Respondent allows to earn revenue by selling click throughs to advertisers who bid for the highest ranking links on the <trademe.com> website. So it could be the goods and services of those advertisers (which are offered for sale on websites to which the links on the <trademe.com> website point) in connection with which the disputed domain name is being used. That would not to our mind be use by the Respondent.

Or it could be that the advertising service offered by HotFarm to those advertisers is the service in connection with which the disputed domain name is being used. That to our mind would not be use by the Respondent. Or it could be the parking monetization service offered by HotFarm to the Respondent that is the service in connection with which the disputed domain name is being used. That is also not use by the Respondent.

Any of those use characterizations is arguable and it seems to us that the language of the Policy is broad enough to encompass each scenario. But none of those offerings is an offering of goods and services by the Respondent even if we take the view that HotFarm is the Respondent's agent and the click through revenue is the ‘rental' the Respondent receives for the hosting of advertiser's links on the <trademe.com> website.

Even if the use could be shown to be use by the Respondent, the next question would be whether that offering was a bona fide offering of goods and services by the Respondent. This Panel takes the view that domain names are a public good and that trading in domain names, which includes assigning or renting them, is not of itself a bona fide use of them by the Respondent, even if it could be characterized as use by the person to whom the domain name is assigned or rented. This Panel's view is that to register domain names and park them to earn rental revenue by allowing a third party to use the domain name itself is not a bona fide use of the domain name in connection with the offering of goods or services by the registrant of that domain name.

In our view, what is required to satisfy paragraph 4(c)(i) is that a disputed domain name resolves to a website under the control of the registrant, or points to nameservers on which such a website is imminently to be located, or to an email gateway with which the domain name is to be used, under the control of the registrant at or through which the registrant's goods or services are offered or otherwise available for use. We could also envisage a case where a domain name was legitimately parked pending other demonstrable preparations to use it in a new venture for example, but we would expect that the temporary nature of the parking would be evident by the time the case comes to the panel for adjudication.

In this case the <trademe.com> website offers nothing that could even remotely be characterized as goods or services of the Respondent, even though the Respondent may receive click through revenue as a result of HotFarm's customers paying a fee to HotFarm for a chosen term to be inserted on the <trademe.com> website. Indeed such use would only reinforce our view that on such basis the Respondent cannot take the benefit of paragraph 4(c)(i) of the Policy.

The next question is whether the Respondent has been commonly known by the domain name, even if it has acquired no trademark or service mark rights. There is no evidence to that effect and the Respondent does not claim the benefit of that provision. We do not think paragraph 4(c)(ii) affords any benefit to the Respondent.

To obtain the benefit of paragraph 4(c)(iii) a respondent has to show that it is making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of a disputed domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue. We are satisfied that the evidence does not show any intent to tarnish the Complainant's TRADE ME brand. Nor does it reveal a non-commercial use of the domain name; on the contrary, the whole objective of the use in this case is to generate commercial revenue. We find that the Respondent is not making a noncommercial use of the disputed domain name.

Is it making a fair use of the disputed domain name? On what basis is “fair” to be judged? In our view the parking of the disputed domain name with HotFarm to be monetized is not a fair use of a public good; on the contrary, on the view we take it is an unfair monopolization of the disputed domain name. Even if the use were fair, it seems to us that the Respondent engages in the monetization exercise with intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers. It is highly unlikely in our view that any consumer would type into their browser address bar “www.trademe.com” and expect to see what is at the <trademe.com> website. If the user is looking for the Complainant they have been mislead, and if they are looking for the Respondent they have equally been mislead, since no product can be acquired from the Respondent at the <trademe.com> website. It seems to us that the majority of parked domain monetization sites rely on a misleading diversion of consumers to a target different from the one that they intended to reach.

In our view the Respondent cannot take the benefit of paragraph 4(c) of the Policy. It nevertheless remains to be decided whether the Respondent has shown independently of paragraph 4(c) that it has rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name. A number of panels have concluded that a respondent may have a right to register and use a domain name to attract Internet traffic based on the appeal of a commonly used descriptive phrase, even where the domain name is identical or confusingly similar to the trademark of a complainant, provided it has not been registered with the complainant's trademark in mind. See, e.g., Bradley D Mittman MD dba FRONTRUNNERS® v. Brendhan Hight, MDNH Inc, WIPO Case No. D2008-1946, National Trust for Historic Preservation v. Barry Preston, WIPO Case No. D2005 0424; Private Media Group, Inc., Cinecraft Ltd. v. DHL Virtual Networks Inc., WIPO Case No. D2004-0843; T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. v. J A Rich, WIPO Case No. D2001-1044; Sweeps Vacuum & Repair Center, Inc. v. Nett Corp., WIPO Case No. D2001-0031; EAuto, L.L.C. v. Triple S. Auto Parts d/b/a Kung Fu Yea Enterprises, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2000-0047.

Thus, where a respondent registers a domain name consisting of a “dictionary” term because the respondent has a good faith belief that the domain name's value derives from its generic or descriptive qualities rather than its specific trademark value, the use of the domain name consistent with such good faith belief may establish a legitimate interest. See Mobile Communication Service Inc. v. WebReg, RN, WIPO Case No. D2005-1304. See also Media General Communications, Inc. v. Rarenames, WebReg, WIPO Case No. D2006-0964 (domain name must have been registered because of, and any use consistent with, its attraction as a dictionary word or descriptive term, and not because of its value as a trademark).

Although we have come to the view that the disputed domain name is not being used in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services by the Respondent, it does not follow that the Respondent has no legitimate interest in connection with that domain name. The Respondent may for example be entitled to use the disputed domain name to point to a website to sell its products or services, or it may wish to simply use the domain name for email purposes. The fact that it is not doing so only deprives it of the benefit of paragraph 4(c) of the Policy. In our view the fact that there are quite plausible and legitimate uses to which the generic term “trade me” could be put, and notwithstanding the Complainant's submission that the words do not denote anything that makes grammatical sense, their generic and non distinctive connotation may be sufficient to give the Respondent a legitimate interest in the disputed domain name if it wished to utilize it for some bona fide purpose. As discussed above, the Respondent has not been able to bring itself within any of the safe-harbours of paragraph 4(c) of the Policy. Accordingly, the determination of legitimacy largely hinges on the question of bad faith which is discussed below. See Media General Communications, Inc. v. Rarenames, WebReg, WIPO Case No. D2006-0964. We also take into account the almost eight years that have passed since the disputed domain name was registered, and the four year delay between the Complainant's commencement of its business in 1999 and it taking steps to apply for a trademark, even in its native New Zealand. On our view those factors combine to increase the potential legitimacy of the Respondent's interest in respect of the disputed domain name

In our view, the question of whether the Complainant has or has not discharged its burden of showing that the Respondent has no legitimate interest in respect of the disputed domain name must ultimately hinge on the question of bad faith, to which the Panel now turns.

Given that the Respondent's registration of the disputed domain name predates by more than two years the Complainant's first application for a trademark incorporating the words “trade” and “me”, the Complainant's case under paragraph 4(a)(iii) of the Policy hinges on whether we accept its contentions that the Respondent must have been aware of the Complainant's business at the time of its registration of the disputed domain name.

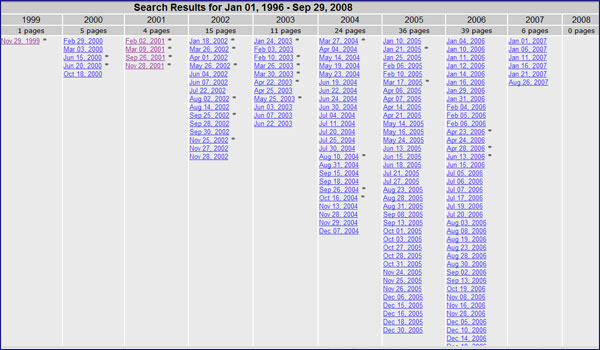

The Complainant asserted that the Respondent had successfully manipulated its website (or the Wayback Machine at “www.archive.org”) so as to prevent the capture and display of its pre-September 2001 website appearance. Below is the Wayback machine's record for the disputed domain name indicating that it has cached versions of the <trademe.com> website going back as far as November 29, 1999:

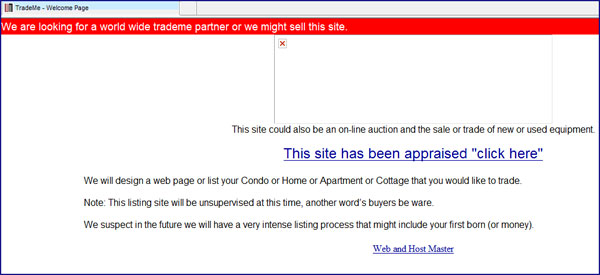

There are eight cached versions of the <trademe.com> website that pre-date the Respondent's registration. The last one captured before the date of registration was on March 9, 2001. The landing page of that website appeared as follows:

The Panel notes the reference under the omitted graphic to the site's potential as “an on-line auction” precisely the Complainant's business, which certainly raises suspicion given that the reference did not appear on the versions of the page before 2001. None of the earlier manifestations of the site, nor any up until about 2005, have any references to New Zealand or on-line auctions. The disputed domain name lapsed and was deleted after the above depicted content was used by the previous registrant of the disputed domain name.

After 2005 the <trademe.com> website began to display occasional links that demonstrated a knowledge of the Complainant's business and geographical location. The Respondent concedes as much but defends itself on the basis that the links in question were not knowingly generated by it and that it cannot be expected to monitor what HotFarm or Yahoo! were doing with the domain name from which it was earning revenue (through their efforts). To allow the argument that a respondent can delegate to others the misleading utilization of its domain name and then claim to have no responsibility for that state of affairs would set a dangerous precedent indeed. If respondents could do that with impunity it would defeat the operation of the Policy. The Respondent is the registrant of the disputed domain name and it is responsible for whatever it allows others to do with that domain name, particularly in return for income. Whether HitFarm is treated as an agent or a subcontractor or a delegate of the Respondent, the activities it engages in have to be imputed to the Respondent as registrant of the domain name unless the Respondent can demonstrate hacking or other clearly unauthorized use of its domain name. No such unauthorized conduct is evident here. Despite the Respondent's contentions that references to online auctions and similar activities, as well as more recent inclusion of phrases idiosyncratically identified with the Complainant's business, were not intentional, we think there has to be a strict liability approach when assessing whether the Respondent is tainted by HitFarm and/or Yahoo! conduct of the kind in question. As a consequence, we incline to the view that the Complainant has shown that the use of the disputed domain name in the period since 2005 has not been bona fide.

Unhappily for the Complainant, and unlike the position under the auDRP where the disjunctive “or” is used between “registered” and “being used” in paragraph 4(a)(iii) of that policy under the .au ccTLD, under the Policy bad faith registration needs to be shown as well as bad faith use. As presaged above, none of the registered trademarks referred to in the Complaint, nor those additionally evidenced in annexures, pre-date the Respondent's registration of the disputed domain name. In fact the Complainant's earliest trademark filing was July 24, 2003, which post dates by more than two years the Respondent's registration of the domain name. That application was not publicly advertised as accepted until September 2003 and the formal registration was not entered until January 2004. This really makes the Complainant's numerous assertions as to the Respondent's knowledge of the Complainant's registered trademarks quite untenable. Nor is there any compelling evidence before the Panel that the Respondent must have registered the disputed domain name with the Complainant and any current or future rights it may obtain specifically in mind. See ExecuJet Holdings Ltd. v. Air Alpha America, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2002-0669; NetDeposit, Inc. v. NetDeposit.com, WIPO Case No. D2003-0365; and AVN Media Network, Inc. v. Hossam Shaltout, WIPO Case No. D2007-1011. To our mind that seals the fate of the Complaint in the present proceedings.

At least as cached by the Wayback Machine, no versions of the <trademe.com> website between July 18, 2001 and mid 2005 have any reference to an online auction. Nor do they reveal anything that would support conclusion that the Respondent was the slightest bit aware of the Complainant. Why should we find that the Respondent ought to have known of the Complainant's business let alone its potential future trade mark registrations in July 2001 without also finding that the Complainant should have known of the use of the disputed domain name since 1999. Indeed had it thought it important to have that name, the Complainant could presumably have secured it as easily as the Respondent did after it lapsed and was deleted in 2001.

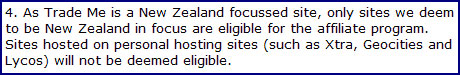

As at July 22, 2001, four days after the Respondent registered the disputed domain name, this is what rule 4 of the Complainant's affiliate program stated (see http://web.archive.org/web/20011024123623/trademe.co.nz/structure/affiliate_prog/):

Consistently with the similar submissions made by the Respondent in relation to the geographical targeting by the Complainant of prospective customers in New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, Australia, we have come to the view that, whilst the Complainant now has an impressive business in New Zealand, it has exaggerated its extra-territorial fame as at July 18, 2001. It really asks us to treat as self evident, propositions which the evidence contradicts.

The Panel does not find the evidence sufficient to demonstrate that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name with the aim of profiting from and exploiting the Complainant's rights in the TRADEME mark. The primary rule in relation to domain name registrations is “first come, first served”, to which the Policy provides a narrow exception. See Macmillan Publishers Limited, Macmillan Magazines Limited and HM Publishers Holdings Limited v. Telepathy, Inc, WIPO Case No. D2002-0658. While the Complainant has rights in TRADEME to the extent of its use as a non-descriptive source indicator for the Complainant's products and services, the mark nonetheless is comprised of a common verb and a common pronoun, which denote a self-promoting item to be traded, and connote a looser theme of trade in goods and services. We agree with the Respondent's submissions to that effect.

As noted above, a number of panels have concluded that a respondent may have a right to register and use a domain name to attract Internet traffic based on the appeal of descriptive or dictionary terms, in the absence of circumstances indicating that the respondent's aim in registering the disputed domain was to profit from and exploit the complainant's trademark. See, e.g., National Trust for Historic Preservation v. Barry Preston, supra. The Policy was not intended to permit a party who elects to register or use a dictionary term as a trademark to thereafter bar others from using the term in a domain name, unless it is clear that the use involved is seeking to capitalize on the goodwill created by the trademark owner. See Match.com, LP v. Bill Zag and NWLAWS.ORG, supra; National Trust for Historic Preservation v. Barry Preston, supra. The use of a domain name for third-party advertising is not per se illegitimate under the Policy, provided that the registration was not seeking to take advantage of the complainant's rights. See, e.g., The Landmark Group v. DigiMedia.com, L.P., NAF Claim No. 0285459.

The Panel notes that paragraph 2 of the Policy implicitly requires some good faith effort to avoid registering and using domain names corresponding to trademarks in violation of the Policy, where a registrant is engaged in the wholesale registration of large numbers of domain names. Media General Communications, Inc., supra. See Shaw Industries Group Inc. and Columbia Insurance Company v. Rugs of the World Inc., WIPO Case No. D2007-1856; HSBC Finance Corporation v. Clear Blue Sky Inc. and Domain Manager, WIPO Case No. D2007-0062. However, paragraph 2 of the Policy has not been read as routinely requiring registrants to conduct trademark searches, see, e.g., Starwood Hotels and Resorts Worldwide, Inc., Sheraton LLC and Sheraton International Inc. v. Jake Porter, WIPO Case No. D2007-1254, and a complainant generally must proffer some evidence, whether direct or circumstantial, indicating that the respondent had the complainant's mark in mind when registering the disputed domain name. See The Skin Store, Inc. v eSkinStore.com, WIPO Case No. D2004-0661.

No such showing has been made by the Complainant in this case. Certainly no trademark search in July 2001 would have revealed the Complainant's trademarks since they were not registered until early 2004. And whilst we think it would not suffice for the purposes of the Policy, there is nothing in the provided record to establish that the Respondent actually knew, reasonably should have known, or could have any constructive notice of the Complainant's common law rights in the TRADEME mark at the time the Respondent acquired the disputed domain name.

The Respondent has been party to a number of UDRP proceedings but this without more does not establish a pattern of abusive domain name registration practices which would necessarily support an inference of the Respondent's bad faith in this case. As the Respondent points out, it has been successful in most of the cases it has defended. It is an accomplished participant in the UDRP process. That gives us cause to be wary of the Respondent's carefully crafted submissions and the statutory declaration in support, but in the end we cannot substitute our intuition or suspicion for evidence, and the Panel is unable to conclude from the totality of the circumstances as reflected in the record that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name with the aim of profiting from or exploiting the Complainant's mark. See CNR Music B.V. v. High Performance Networks, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2005-1116.

Despite the requirement that the Complainant prove both registration and use in bad faith, paragraph 4(b) of the Policy provides a mechanism by which certain types of non bona fide use can constitute evidence of both registration and use in bad faith. Accordingly, it is necessary to explore whether any of the provisions of that paragraph can be taken advantage of by the Respondent. It states that any of the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation, shall be considered evidence of the registration and use of a domain name in bad faith:

(i) circumstances indicating that the respondent registered or acquired the domain name primarily for the purpose of selling, renting, or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the complainant (the owner of the trademark or service mark) or to a competitor of that complainant, for valuable consideration in excess of documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the domain name; or

(ii) circumstances indicating that the respondent registered the domain name in order to prevent the owner of the trademark or service mark from reflecting the mark in a corresponding domain name, provided that the respondent has engaged in a pattern of such conduct; or

(iii) circumstances indicating that the respondent registered the domain name primarily for the purpose of disrupting the business of a competitor; or

(iv) circumstances indicating that the respondent intentionally is using the domain name in an attempt to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its website or other on-line location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant's mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of the respondent's website or location or of a product or service on its website or location.

The examples of bad faith registration and use set forth in paragraph 4(b) of the Policy are not meant to be exhaustive of all circumstances from which such bad faith may be found. See Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003. The overriding objective of the Policy is to curb the abusive registration of domain names in circumstances where the registrant is seeking to profit from and exploit the trademark of another. Match.com, LP v. Bill Zag and NWLAWS.ORG, WIPO Case No. D2004-0230.

The Panel has already expressed the view that the Respondent did not on the provided record register the disputed domain name in bad faith, and there is no evidence before the Panel that would attract the operation of subparagraphs 4(b)(i) to (iii) which all exemplify bad faith registrations. What makes paragraph 4(b) important in so many cases is that subparagraph 4(b)(iv) addresses only current use by a respondent yet, where non-bona fide current use is proven, that conduct is deemed to be evidence of bad faith use and bad faith registration. Absent evidence of good faith registration, this deemed evidence can be pivotal to many cases. Whether that outcome is the result of inelegant drafting or intentional given the objectives of the Policy is not for us to consider; it is without doubt the way the Policy has been interpreted and applied since its inception, and we embrace it.

Paragraph 4(b)(iv) requires the Complainant to prove that, by using the disputed domain name, the Respondent has intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its web site or other on-line location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant's mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of the respondent's web site or location or of a product or service on its web site or location. Here the objective intent of the Respondent is the relevant test, to the extent to which that can be ascertained or inferred. Thus, although in our view the Respondent is liable for the acts of its agents/contractors or delegates, it does not thereby attract the operation of clause 4(b)(iv) of the Policy unless it also has the objective “intent” to achieve one of the proscribed purposes. In our view the Respondent, by Mr. Park's declaration, has assiduously declared that it had no such objective intent. It may be that a Court, with a fuller record and opportunity to interrogate evidence and cross-examine witnesses might reach a different conclusion. But that is not the Panel's role in the present expedited proceedings under the Policy. Absent any basis for disbelieving Mr. Park, the Panel cannot afford the benefit of paragraph 4(b)(iv) to the Complainant.

The Panel therefore concludes that the Complainant has failed to satisfy its burden of showing bad faith registration of the disputed domain name by the Respondent on July 18, 2001. It has therefore failed to make good the essential third limb of its Complaint under paragraph 4(a)(iii) of the Policy.

For all the foregoing reasons, the Complaint is denied.

Philip N Argy | |

Sir Ian Barker | David Sorkin |

Dated: April 7, 2009