The Complainant is Scrum Alliance, LLC, United States of America (“United States”), represented by Jackson Walker, LLP, United States.

The Respondent is Contact Privacy Inc. Customer 1247644697, Canada / Matthew Barcomb, United States of America.

The disputed domain name <scrumsalliance.org> (the “Disputed Domain Name”) is registered with Google LLC (the “Registrar”).

The Complaint was filed with the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (the “Center”) on September 6, 2021. On September 7, 2021, the Center transmitted by email to the Registrar a request for registrar verification in connection with the Disputed Domain Name. On September 7, 2021, the Registrar transmitted by email to the Center its verification response disclosing registrant and contact information for the Disputed Domain Name that differed from the named Respondent and contact information in the Complaint. The Center sent an email communication to the Complainant on September 8, 2021, providing the registrant and contact information disclosed by the Registrar, and inviting the Complainant to submit an amendment to the Complaint. The Complainant filed an amended Complaint on September 13, 2021.

On September 9, 2021, the Respondent sent a communication to the Center to which the Center acknowledged receipt.

The Center verified that the Complaint together with the amended Complaint satisfied the formal requirements of the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Policy” or “UDRP”), the Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Rules”), and the WIPO Supplemental Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Supplemental Rules”).

In accordance with the Rules, paragraphs 2 and 4, the Center formally notified the Respondent of the Complaint, and the proceedings commenced on September 14, 2021. In accordance with the Rules, paragraph 5, the due date for Response was October 4, 2021. The Respondent filed his Response with the Center on September 29, 2021.

The Center appointed David H. Bernstein as the sole panelist in this matter on October 4, 2021. The Panel finds that it was properly constituted. The Panel has submitted the Statement of Acceptance and Declaration of Impartiality and Independence, as required by the Center to ensure compliance with the Rules, paragraph 7.

Pursuant to paragraph 10(c) of the Rules, the Panel set October 25, 2021 as the expected date for decision.

The Complainant is a Colorado nonprofit corporation that serves as a professional membership organization for practitioners of “Scrum,” a product management framework that is often used in software development.1 The Complainant provides training and professional accreditation to individuals who use or hope to use the Scrum framework. The Complainant has used the name SCRUM ALLIANCE in connection with this training and accreditation as well as in connection with hosting events and providing other association services.

The Complainant owns a number of United States Trademark Registrations, including:

- SCRUM ALLIANCE (Registration No. 3,548,753), registered on December 23, 2008, for training, mentoring, and tutoring services;

- SCRUM ALLIANCE (Registration No. 3,622,159), registered on May 19, 2009, for association services as well as training, mentoring, and tutoring services (Design Mark);

- SCRUM ALLIANCE (Registration No. 4,017,468), registered on August 30, 2011, for indicating memberships in an organization of product developers and manufacturers.

The Complainant operates its principal website at the domain name <scrumalliance.org>. An excerpt of its home page is shown below:

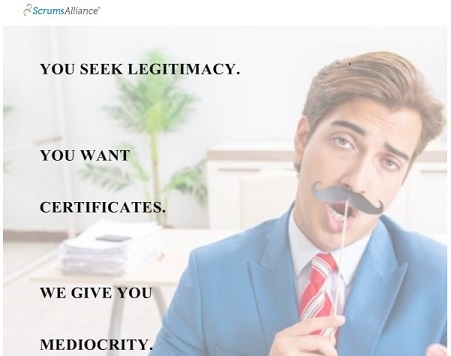

The Respondent is a professional who has used Scrum and related frameworks in his work since 2006. The Respondent registered the Disputed Domain Name on July 7, 2020 and operates a parody website at that address that mocks the Complainant. The website uses parody and humor to suggest that the training and certification offered by the Complainant under the SCRUM trademark is a fig leaf marketed to companies that want to seem innovative by associating themselves with the SCRUM framework. The website employs profanity and displays a logo that is similar to the design mark registered by the Complainant. An image of the Respondent’s website as of the filing of the Complaint is shown below:

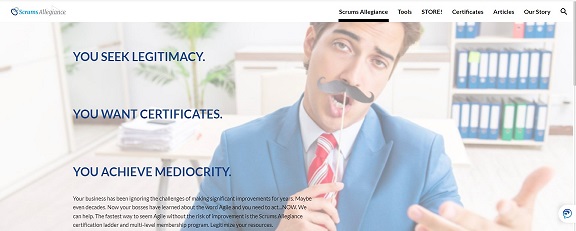

Following the filing of the Complaint, the Respondent created a new website at “www.scrumsallegiance.org.” The Respondent now redirects visitors to the Disputed Domain Name to that new website. The <scrumsallegiance.org> domain name (which is not at issue in this proceeding) and website features a version of the parody logo that is slightly different from the one featured in the website to which the Disputed Domain Name originally resolved. This updated version of the webpage also contains additional sections, including a “STORE!” section that sells parody items based on the parody in the website. An image of the Respondent’s new website appears below:

The Complainant contends that the Disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to its registered marks that contain, or are entirely composed of, the phrase “Scrum Alliance.” The Complainant argues that the “Respondent’s insertion of the letter ‘s’ in the middle of ‘Scrum Alliance’ is a textbook example of typosquatting.”

The Complainant further contends that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name because the Respondent has no registered trademarks or trade names corresponding to the Disputed Domain Name and no authorization to use the SCRUM ALLIANCE trademark. The Complainant adds that the Respondent cannot invoke the circumstances described in paragraph 4(c) of the UDRP because the Respondent has not used the Disputed Domain Name for a bona fide offering of goods or services, the Respondent registered the Disputed Domain Name too recently to be commonly known by it, and the Respondent cannot engage in legitimate noncommercial use of a Disputed Domain Name that so closely resembles the Complainant’s registered trademarks.

Finally, the Complainant argues that the Respondent registered and used the Disputed Domain Name in bad faith. First, the Complainant contends that the Respondent is a competitor, in the broad sense given to that term in the Policy, and is using the Disputed Domain Name to disrupt the Complainant’s business. Second, the Complainant argues that the mere fact that the Disputed Domain Name is misleading amounts to bad faith. Third, the Complainant points to the Respondent’s use of a privacy shield service as contributing to “the accumulation of elements” that amount to bad faith.

The Respondent centers his argument on the fact that the Disputed Domain Name hosts a parody website.

With respect to the first element of the Policy, the Respondent “acknowledges that the Disputed Domain Name alone is confusingly similar with the Complainant’s trademark.”

The Respondent nevertheless argues that the Disputed Domain Name, which resolves to a parody website, is a legitimate noncommercial fair use under paragraph 4(c) of the Policy. The Respondent explains that his intention is to use parody to “highlight an ongoing issue in the [Scrum] community” and that, by virtue of its success, the Complainant has become a “cultural symbol” and an appropriate “target for parody.” The Respondent alleges that he solicited feedback about the website from both fellow critics and the Complainant’s membership, and none of those individuals “were confused about its intention as obvious parody and satire.” Finally, the Respondent explains that he carefully chose the misspelling in the Disputed Domain Name to avoid a “common typo” and disseminated its contents primarily via social media where it would not misleadingly divert consumers from the Complainant’s website. The Respondent argues that this form of parody and satire “is a legitimate use and interest in the Disputed Domain.”

The Respondent addresses the argument that his registration and use of the Disputed Domain Name was in bad faith in several ways. First, the Respondent clarifies that his website does not offer any similar or competing service and alleges that any commercial activity on the website is incidental to its primary purpose: parody and satire. Second, the Respondent alleges that he sought to avoid misleading visitors about his potential affiliation with the Complainant by disseminating the website via social media and refraining from search engine optimization tactics. Third, the Respondent argues that he is not a competitor because he does not “oppose” the Complainant. The Respondent argues that he has targeted the Complainant merely as a symbol of a larger problem in their shared industry. Finally, the Respondent explains that his use of a privacy shield to register the Disputed Domain Name is not evidence of bad faith because it has become a common practice and the default setting when using the Respondent’s registrar, and because he wanted to avoid receiving spam emails.

Under paragraph 4(a) of the Policy, in order to prevail, the Complainant is required to prove each of the following by a preponderance of the evidence:

(i) The Disputed Domain Name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the Complainant has rights; and

(ii) The Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the Disputed Domain Name; and

(iii) The Disputed Domain Name has been registered and is being used by the Respondent in bad faith.

For the reasons stated below, the Panel finds the Complainant has not proven all three of these elements.

The Complainant has clearly established trademark rights in SCRUM ALLIANCE based on its federal trademark registrations. The Complainant has two trademark registrations for the term SCRUM ALLIANCE by itself and one where SCRUM ALLIANCE is the dominant feature of the mark. The Respondent does not contest the Complainant’s rights in the SCRUM ALLIANCE mark.

The Respondent also does not contest that the Disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s trademark for purposes of the Policy. The Disputed Domain Name differs from the Complainant’s trademarks only by the addition of a single letter – the letter “s” – in the middle of the Disputed Domain Name. As such, there is no credible dispute as to the confusing similarity of the Disputed Domain Name for purposes of the Policy.

Accordingly, the Panel concludes that the Disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to the SCRUM ALLIANCE trademark under paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy.

Under paragraph 4(c) of the Policy, the Respondent may establish rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name by demonstrating the following:

(i) before any notice of the dispute, the Respondent’s use of, or demonstrable preparations to use the Disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services; or

(ii) the Respondent has been commonly known by the Disputed Domain Name, even if he has acquired no trademark or service mark rights; or

(iii) the Respondent is making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the Disputed Domain Name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue.

The Respondent primarily argues that he has made a noncommercial or fair use of the Disputed Domain Name by hosting a pure parody website at the website to which the Disputed Domain Name resolves. He argues that this parody website constitutes legitimate criticism.

The WIPO Overview 3.0 reflects that a consensus has developed amongst WIPO panelists with respect to the question of when a criticism site can support a respondent’s assertion of rights or legitimate interests. Under this consensus position, previous UDRP panels have tended to find that, where the domain name at issue is identical to a complainant’s trademark, the registration and use of such a domain name likely would not be legitimate because the use of such a domain name “creates an impermissible risk of user confusion through impersonation.” WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.6.2. The key, therefore, in assessing whether a respondent has a right or legitimate interest to use a domain name for a criticism site in cases involving a domain name “identical to a trademark” is whether the domain name and website create a “risk of user confusion through impersonation.” Id.

This case is not exactly a case involving an “identical” domain name because the Respondent has added the letter “s” in the middle of the domain name. But that is a subtle difference that may be lost on some Internet users. However that may be, and in particular for present purposes of assessing the second element, overall, there is no risk of confusion through impersonation here. In the specific context of this case, the website so overwhelmingly rebuts any risk of impersonation that no reasonable Internet user would be confused into thinking that this website comes from the Complainant. The image of a clownish man holding a fake mustache on a stick, and his obvious parodic facial expression, immediately conveys that this website is not from the Complainant. The distinction between this website and the Complainant’s website is reinforced by the parody headline that states “You Seek Legitimacy. You Want Certificates. We Give Your Mediocrity” (or “You Achieve Mediocrity”). No one could realistically read that and believe the website is impersonating the Complainant.

Contrary to being a website (or domain name, albeit a closer call) that impersonates the Complainant, the Respondent’s website is instead a textbook parody. As the United States Supreme Court has taught, for a parody to be effective, it needs to create “tension between a known original and its parodic twin.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 588 (1994). “When parody takes aim at a particular original work, the parody must be able to ‘conjure up’ at least enough of that original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable.” Id. The Respondent’s website accomplishes those goals – it conjures up the Complainant’s website with its subtle typo in the Disputed Domain Name, with the subtle change to the logo, with its display of a person practicing the framework (or seeking certification), and with its use of three prominent headlines on its homepage, but it modifies each of these elements in ways that distinctly communicates its parodic message.

The fact that the Disputed Domain Name differs from the Complainant’s trademark by the addition of only a single letter does make this a close case. But, when it comes to parody or criticism websites, the context of the website should be considered along with the domain name when assessing rights or legitimate interests. Panels should not rule based only on a myopic assessment of the domain name itself. As recently acknowledged in Florida Power & Light Company v. Registration Private, Domains By Proxy, LLC / Alex Patton, Ozean Media, and Conservatives for Responsible Stewardship, WIPO Case No. D2021-2526, although “’the correlation between a domain name and the complainant’s mark is often central’” to the inquiry of whether a domain name falsely suggests affiliation, it is not the only relevant evidence (quoting WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.5). Further, although “[d]omain names identical to a complainant’s trademark ‘carry a high risk of implied affiliation,’” id. (quoting WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.5.1), that risk may be mitigated based on “circumstances beyond the disputed domain name itself,” including an assessment of “the Respondent’s website.” Id. As in the Florida Power & Light Company case, the website in this case “is by all appearances genuinely noncommercial, and the use of the Complainant’s mark is mainly referential, on a site devoted to commentary and criticism.” Id.

This case is therefore not like the situation in Dover Downs Gaming & Entertainment, Inc. v. Domains By Proxy, LLC / Harold Carter Jr, Purlin Pal LLC, WIPO Case No. D2019-0633, where the respondent’s domain name was being used for an alleged criticism cite that really was a pretext for extortion. Here, in context, the website is authentically a pure parody site. That said, should the Respondent try in the future to profit off of the Complainant’s trademark through the Disputed Domain Name that might be the kind of changed circumstance that would justify a refilling and a reassessment of the whether the Respondent’s use is legitimate. See WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.18.

To be clear, this Panel continues to ascribe to the view expressed in Dover Downs Gaming & Entertainment, Inc. that panels should “support the developing consensus around the impersonation test, even for cases, like the one here, between United States parties and with a United States panelist and where the location of mutual jurisdiction is in the United States.” Fealty to that principal, though, requires a rigorous assessment of whether the domain name and website at issue are likely to be seen as impersonating the Complainant. When such impersonation exists, U.S. courts and UDRP panels do not hesitate to find that the conduct is cybersquatting or otherwise violative of a trademark owner’s rights. E.g., Planned Parenthood Fed’n of Am., Inc. v. Bucci, 42 U.S.P.Q.2d 1430 (S.D.N.Y. 1997), aff’d, 152 F.3d 920 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 834 (1998) (enjoining critic’s website that impersonated the Planned Parenthood website); Northwestel Inc. v. John Steins, WIPO Case No. D2015-0447 (transferring website that was allegedly a criticism site but was a pretext for cybersquatting). Where they do not find impersonation or cybersquatting intent, panels should find such websites to be a fair use under the Policy, as U.S. courts do as well. See, e.g., Florida Power & Light Company, supra; Northland Ins. Cos. v. Baylock, 115 F. Supp. 2d 1108, 1117 (D. Minn. 2000) (plaintiff failed to show a sufficient likelihood of confusion among consumers to justify the issuance of a preliminary injunction against a criticism site).2

The Panel appreciates that the Complainant may not be amused by the Respondent’s website. It may even be the case that the Respondent’s criticisms are unfair. But, however offensive the parody may be to the Complainant, the website and Disputed Domain Name (albeit to a much finer degree) cannot be seen as impersonating the Complainant on the facts of this case.

For the foregoing reasons, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not established that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name.

Even if the Complainant had shown that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name, the Complaint would still fail because the Complainant has not established that the Respondent registered and used the Disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

First, citing paragraph 4(b)(iii) of the Policy, the Complainant argues that the Respondent is a “competitor” who primarily used the Disputed Domain Name to disrupt its business. Although it is true that the term “competitor” has, in some cases, been interpreted broadly in the context of the Policy, being a “competitor” still requires that a respondent act “for some means of commercial gain, direct or otherwise,” and that the respondent has used that competitive position to disrupt the complainant’s business. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.1.3. The Respondent is not a competitor under this understanding; rather, he has published a purely noncommercial parody website. The Complainant has not alleged that Respondent sought to gain anything, commercial or otherwise, by registering the Disputed Domain Name and using it to host his parody website. Non-pretextual criticism is not prohibited by the Policy and does not render the parodist or critic a “competitor.” Id. (the activities of a “competitor” under paragraph 4(b)(iii) of the Policy “would not encompass legitimate noncommercial criticism”); Dover Downs Gaming & Entertainment, Inc. (“Non-pretextual criticism (even if one believes the criticism to be unfair) is not prohibited by the Policy.”).

The Panel notes that the Respondent’s revised website has added a “STORE!” link at which the Respondent sells merchandise that reinforces his parody message, such as mugs that display the parody phrase ”Buy Certificates – Legitimize Your Resources – That’s Not Scrums.” The Respondent explains that the revenue earned from these sales is being used to offset the cost of operating the website. That type of minimal commercial activity is not inconsistent with a claim that the Respondent has a legitimate interest in using the Disputed Domain Name for a criticism or parody website, and that its use is not in bad faith. Cf. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.6.3 (“[s]ome panels have found (…) that a limited degree of incidental commercial activity may be permissible in certain circumstances (e.g., as ‘fundraising’ to offset registration or hosting costs associated with the domain name and website”); see also id., section 2.5.3 (in considering the impact of commercial activity on a website, “whether a respondent’s use of a domain name constitutes a legitimate fair use will often hinge on whether the corresponding website content prima facie supports the claimed purpose (e.g. for referential use, commentary, criticism praise or parody), is not misleading as to source or sponsorship, and is not a pretext for tarnishment or commercial gain”).

Second, citing Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Domains by Proxy, LLC/UFCW Int’l Union, WIPO Case No. D2013-1304, the Complainant argues that the use of a misleading domain name can itself support a finding of bad faith. But whether a potentially misleading domain name supports a finding of bad faith is a fact-specific inquiry. In the Wal-Mart case, the panel found bad faith because the domain name, <reallywalmart.com>, suggested that the website was “really” from Wal-Mart. Moreover, in that case, the respondent’s website did not clearly alert users that the “website [was] unaffiliated with Complainant.” Id. That is not the case here; although the Disputed Domain Name flirts with misrepresenting that it is associated with the Complainant (less so with the “allegiance” variation to which it now redirects), the website content makes it clear that the website is unaffiliated with the Complainant.

Third, the Complainant claims bad faith based on the fact that the Respondent registered the Disputed Domain Name using a privacy shield to conceal his identity. The use of a privacy shield or proxy service may be indicative of bad faith if such services are used to hide cybersquatting conduct—for example, by preventing a complainant from determining whether a respondent is guilty of a pattern of registering domain names in order to prevent the owner of the trademark from reflecting its mark in a domain name or hiding the date on which a respondent acquired the domain name. See, e.g., Halle Berry and Bellah Brand Inc. v. Alberta Hot Rods, WIPO Case No. D2016-0256. The use of proxy or privacy services does not, however, constitute bad faith where a respondent has a legitimate reason for such use, such as if a respondent seeks to protect his identity as a whistleblower or critic who may be fearful of reprisals. Ustream.TV,Inc. v. Vertical Axis, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2008-0598 (observing that “privacy shields might be legitimate in some cases—such as protecting the identity of a critic against reprisal”); see also E. Remy Martin & C° v. J Pepin – Emedia Development LTD, WIPO Case No. D2013-1751 (concluding the respondent’s use of a privacy service was not bad faith where there was insufficient evidence to show the respondent “attempted to game the UDRP process”). Here, the Respondent did not indicate that he feared reprisal but instead stated that the domain registrar offered the privacy shield as a default option and that the Respondent accepted that option because he wanted to avoid spam (the latter excuse being less credible than the former given that WHOIS no longer routinely publishes registrant’s email address). In the absence of allegations suggesting a different motive, this explanation is sufficient to conclude that the Respondent did not act with subjective bad faith on account of his use of a privacy shield.

The Panel therefore concludes that the Disputed Domain Name was neither registered nor used in bad faith.

For the foregoing reasons, the Complaint is denied.

David H. Bernstein

Sole Panelist

Date: October 25, 2021

1The Amended Complaint lists the Complainant as “Scrum Alliance, LLC” while describing the Complainant as a nonprofit corporation rather than a limited liability company. Amended Complaint, at ¶ 2, 12. The trademark registrations on which the Complainant relies are owned by Scrum Alliance, Inc. Because this discrepancy does not impact the Panel’s consideration of the Complaint, the Panel did not seek clarification from the Complainant on its actual name or corporate form.

2 This Panel’s dicta in Dover Downs Gaming & Entertainment, Inc., supra, which suggested that only the domain name should be considered in assessing impersonation, does not give sufficient deference to all of the factors that should be considered in assessing impersonation. A more nuanced assessment of all the factors is required. Florida Power & Light Company, supra; cf. Network Automation, Inc. v. Advanced Systems Concepts, 638 F.3d 1137, 1148 (9th Cir. 2011) (likelihood of confusion should be analyzed flexibly as some factors “may emerge as more illuminating on the question of consumer confusion”).