Antimicrobial Resistance: A Silent, Looming Global Health Crisis

October 2, 2023

Since their discovery nearly nine decades ago, antibiotics have transformed the world of modern medicine. They have been instrumental in combating deadly and debilitating illnesses and have saved countless lives. Yet the misuse of antibiotics poses risks to public health. As antibiotics become more commonly prescribed and misused, bacteria are developing the capability to resist them, which can undermine the effectiveness of these drugs. Antibiotic resistance can undermine one of the greatest medical breakthroughs, making it a concern for policymakers worldwide.

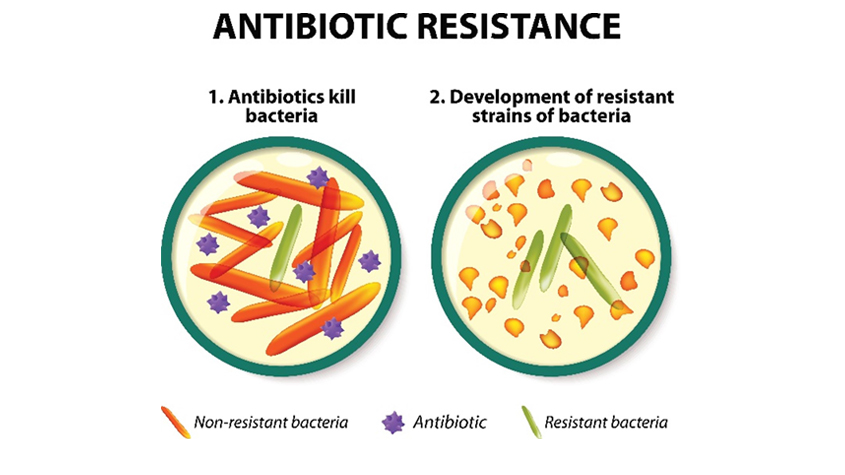

The discovery of Penicillin in 1928 as the world’s first antibiotic marked a watershed moment in medical advancement, dramatically slashing mortality rates and raising life expectancy on a global scale. Yet, a mere 90 years later, we are witnessing the waning efficacy of these “wonder drugs.” Infectious diseases once rendered innocuous by antibiotics are regaining their virulence. The mechanisms may vary, but the outcome remains unerringly consistent: bacteria are evolving to resist the very drugs developed to neutralize them. The natural selection process ensures that these antibiotic-resistant strains not only survive but proliferate, passing on their hardy genetic traits to succeeding generations.

The alarming costs of AMR

The financial and human cost of rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is alarming. According to projections, the economic fallout by 2050 could exceed US $2 trillion globally, pushing 28 million people into poverty. Recent studies, such as one published in The Lancet in 2022, amplify these concerns, attributing close to five million deaths in 2019 to drug-resistant bacterial infections. The same study reveals that AMR currently ranks as the third leading cause of death worldwide, only exceeded by heart disease and stroke, outstripping fatalities from HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, and malaria.

Impact on Sustainable Development Goals

But the reach of AMR’s threat extends further, tangibly impacting most of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), from poverty and inequality to animal welfare. SDG 3: “Good health and well-being” most directly responds to AMR. In 2019, a new AMR indicator was included in this SDG monitoring framework. This indicator monitors the frequency of reported bloodstream infections due to two specific drug resistant pathogens: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); and E. coli resistant to third generation cephalosporins (3GC).

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics

Navigating AMR calls for an examination of its root causes, which can be clubbed into four overarching categories: overuse and misuse in humans, similar malpractices for animals rearing, discharge of untreated solid and liquid waste from hospitals, and industry and human waste. Climate change and air pollution further complicate the tableau, intensifying the frequency and scope of disease outbreaks exacerbating the burden of infectious disease.

Over-prescription and self-medication of antibiotics are part of the problem related to overuse and misuse by humans. A 2017 World Bank study in six developing nations revealed that over 60% of pharmacy visits culminated in antimicrobials dispensing without a clinical diagnosis. This issue is by no means confined to primary care; a separate study suggests that nearly a third of antibiotic prescriptions in United States’ emergency rooms, and 40% of antibiotics for patients before surgery and receiving chemotherapy in Australia, were inappropriate. A 2022 WHO study based in Europe concluded that one in two patients used leftover antibiotics from a previous prescription or obtained them without a prescription. This propensity for self-medication, likely even more prevalent in developing countries, may be due to lack of awareness, prohibitive healthcare costs and limited accessibility to quality care.

In essence, AMR is a series of interlinked challenges of ensuring availability, affordability (access issues), and sustainable use of antibiotics (conservation and stewardship), combined with the need to develop diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics (innovation) that would lessen the need for antibiotic use.

Limbo in pharmaceutical innovation

Perhaps the biggest challenge lies in the arena of innovation – or rather, the lack thereof. For instance, as of 2019, only six of the 32 antibiotics in the clinical development stage that address the WHO’s list of priority pathogens could be termed “innovative”, based on WHO’s innovation criteria comprising of new chemical class, new target and mode of action against the pathogen, and the absence of known cross-resistance of the pathogen. Another study notes that only 16% of new antibiotics in the development pipeline (seven out of 43) can be labeled as “groundbreaking”. The challenge for innovation may further relate to alignment of economic incentives and dynamics of the pharmaceutical market and other stakeholders.

Discrepancies in innovation

Intellectual property (IP) rights, including patents, can work as instruments to stimulate research and development (R&D in health technology, including drugs, diagnostics, and therapeutics. IP rights can allow time-bound market exclusivity – working as rewards for the significant investments like financing, intellectual capital and a vast array of resources required for R&D – while also acting as intangible assets enhancing market value of different stakeholders. For instance, in the 1950-60s, pioneering antibiotics like streptomycin were developed based on research collaboration between Rutgers University and Merck, and supported by patent rights.

Recent trends suggest a nuanced market and R&D landscapes. Small biotech firms and academic research centers are increasingly at the forefront of AMR solutions, sometimes attracting investments from major pharmaceuticals. United States-based Forge Therapeutics, for instance, in 2020 secured a significant agreement with Roche, a major Switzerland-based pharmaceutical firm, for an antibiotic targeting treatment-resistant bacterial infection. The deal brought Forge a sizable incentive for researching AMR issues. Other firms like Sanofi have also embarked on new initiatives such as technology transfers to facilitate local antibiotic production in Nigeria.

Motivations leading to health technology innovation are complex and extend beyond pure financial gain. Partnerships among various stakeholders are emerging, which may lead to a broader shift in pharmaceutical strategy and behavior. These partnerships are driven by both traditional and new and open R&D models that could respond to challenges posed by AMR.

Addressing AMR through collaboration

In addition to more traditional in-house R&D by pharmaceutical companies, two pioneering organizations that are making headway in antibiotic research are the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP) and Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X). GARDP accelerates R&D and promotes access of treatments for drug-resistant infections by working with private, public, and non-profit partners. CARB-X acts as a global talent scout and mentor for nascent antibacterial technologies, propelling these technologies through the crucible of clinical trials.

New licensing agreements

In 2022, GARDP secured a licensing and technology transfer agreement with Shionogi, a Japan-based pharmaceutical firm, to expand and accelerate access to antibiotic treatment against certain bacterial infections in adult. The collaboration between GARDP, Shionogi, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) represents a breakthrough in using voluntary licensing to enable access to newer antibiotics. This license agreement holds strategic significance as it is the first focusing on an antibiotic driven by public health priorities. Equally significant is that the license has been provided by one of the few mid- or large-sized pharmaceutical companies with an active antibiotic development portfolio.

More recently, in 2023, GARDP signed a sublicense agreement with Orchid Pharma Ltd., an India-based pharmaceutical firm. The manufacturing sublicense agreement has important access, environmental, and stewardship provisions, including cost-plus pricing, with a commitment to lower the costs based on volumes to help keep the product affordable for patients and health systems in low-resource settings.

Need to realign global health strategy and priorities

The fight against AMR requires more than acts of philanthropy, aligning market incentives and technical ingenuity; it also demands a shift in global health strategy and priorities. The WHO, for instance, have made strides with systems like the Antibiotic Classification system (AWaRe) to optimize antibiotic stewardship and emphasize the importance of proper use. It also launched the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), which is the first global collaborative effort to standardize AMR surveillance. However, in Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMICs), the use of surveillance programmes remains scarce, making it difficult to map out the need for a specific product.

One Health and AMR

Addressing AMR requires a shift in global health strategy, aligning with One Health principles. One Health refers to an integrated, multidisciplinary, and multi-sectoral approach towards addressing global health challenges, including AMR, that brings in non-health actors and sectors. A Quadripartite Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by WHO, World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in 2022. This agreement provides a formal framework for the four organizations to tackle AMR challenges at the human, animal, plant, and ecosystem interface using a more integrated and coordinated approach. Based on this MoU, the quadripartite developed the One Health Joint Action Plan (2022-2026) which aims to drive the change and transformation required to mitigate the impact of current and future health challenges at the human-animal-plant-environment interface at global and national level. WIPO also actively supports the on-going work on One Health.