Matt Chiu describes his daughter, Amber, as the kind of toddler who liked to run and roll around in mud. She would often drop her dummy on the ground, where the saliva-coated object would immediately gather dirt. Tears and tiny tantrums would follow when Amber realized that she would not get her pacifier back until it had been properly cleaned. That gave her dad an idea.

There are almost 2,000 pacifier patents in the WIPO database alone, making the binky, soother or dodie an object of interest for inventors as much as an object of desire for infants and stressed parents.

Soothing objects were mentioned in medical literature as early as 1473. Before the advent of rubber, plastic or silicone, babies would suckle on homemade coral or ivory teats, or simple cloths infused with something sweet.

The baby must-haves were first patented in the early 1900s. Manhattan pharmacist Christian W. Meinecke registered a teat-and-shield model as design patent number 33,212 in 1900. Three years later, Harvey Spencer registered a “baby comforter” as patent number 745,920. The first registered pacifiers looked more like chess pieces than the dummies we think of today. More than a century on, though, the object still captures inventors’ imaginations – including Matt’s.

Reinventing everyday objects

Following a day out with Amber in 2021, Matt, who holds a PhD from the Singapore University of Technology and Design, used his 3D printer to create a new kind of dummy, designed to be beautiful and hygienic. He called it the Hanabii Pacifier.

“When you are accepted into the Inventor Assistance Program, IPOS matches you with a pro bono patent attorney or agent to help with the patenting process.”

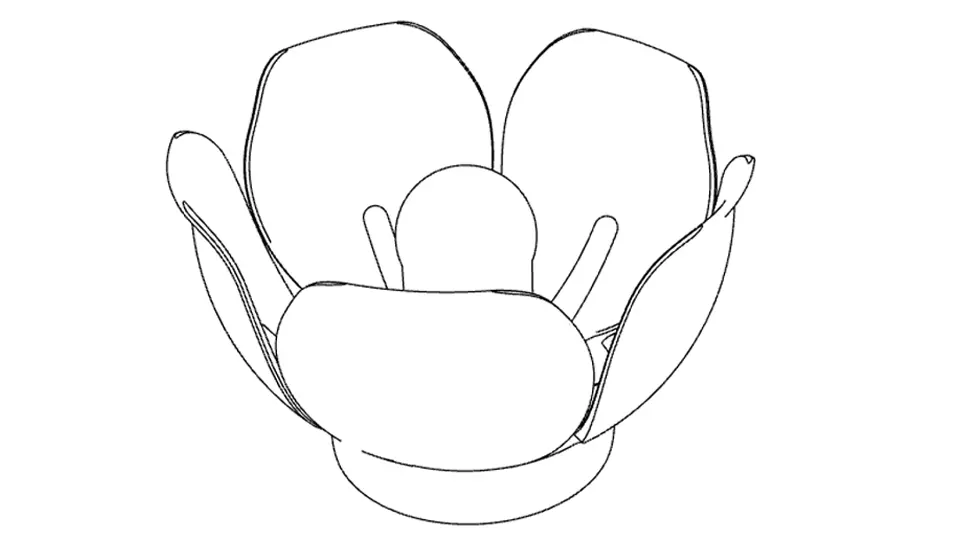

In Japanese, hanabii means “fireworks” and the character for hana means “flower”; the design draws inspiration from both.

Petal-like soft silicone wings encapsulate the teat and protect it when not in use. They open to form a blossom around the baby’s mouth, held by the sucking, and close the moment the dummy leaves the mouth (and hits the ground). The wings also help to keep the pacifier clean in pockets and bags.

According to Cognitive Market Research, the global market for baby pacifiers was worth over US$400 million in 2024, with a compound annual growth rate of 6.00% from 2024 to 2031. WIPO data on patent filings show a long-term growth rate of about 4.8% (CAGR) in the last 20 years (2004–2024).

At least one of the almost 2,000 pacifier patents in the WIPO database pertain to a pacifier designed to help administer drugs (WO/2021/256976). An inventor from the Republic of Korea filed a patent for a mask with an integrated dummy (1020210037006) in 2021. US patent 15782851, filed in 2017, describes a “Smart Pacifier” with sensors that relay data when the user engages the nipple portion. And 06898188, a US patent filed in 1986, features an internal LED light bulb so that parents can better position it in their baby’s mouth in the dark.

Even the Hague Express Database for international design registrations counts 29 comforter-related designs under the search term “pacifier”. They look like butterflies, panda bears or futuristic joysticks.

In the United States, “binky” has become synonymous with pacifiers. Playtex, however, registered the “Binky” trademark in 1935. The development from trademark to generic name is referred to as genericide; hoover, kleenex and zipper are other examples. For that reason, Playtex continues to claim that its product is “the original binky.”

Protecting the pacifier

The Hanabii Pacifier as it is today has gone through more than 30 iterations. Only the concept remains unchanged. Matt began thinking about intellectual property (IP) early. He knew that he wanted to protect his creation, but he did not know how.

An email from the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) changed that. IPOS and WIPO announced a new program that was precisely what Matt needed. He signed up for the Inventor Assistance Program (IAP) in 2023 and became the first Singaporean participant to submit a patent application.

“We are trying to maximize our time during the Patent Cooperation Treaty by having the most outreach.”

“When you are accepted to the program, IPOS matches you with a pro bono patent attorney or agent,” says Matt. For a young inventor worried that he could not afford such services, that was a “golden opportunity”. The program helped him to “break down this mental barrier and made IP more approachable”.

It is still a complex process, however. “I thought it was just about filing it, but it’s not,” he says. His agent, James Kinnaird from Marks & Clerk Singapore, allowed him “to get a lot of insight into this previously very daunting process,” says Matt.

Initially, Matt filed a provisional utility patent application in Singapore. He says that “starting with a provisional patent application, where the claims are roughly there”, helped him to protect his invention early.

The Hanabii company, which is marketing the pacifier, then filed an international patent application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which allows inventors to seek patent protection in multiple countries at once.

The patenting and marketing journey

Matt says the patenting process is an integral part of the Hanabii business model and likens it to a “reserve” to get a better sense of the idea and markets. “We are trying to maximize our time during the PCT [process] by having the most outreach.”

“Our strategy is to launch a worldwide Kickstarter campaign in spring 2025, to attract attention to the product and to look for distributors internationally.” According to Matt, this will help Hanabii to “keep an open mind” regarding which territories to focus on, which in turn will help the company to decide in which countries to enter the national phase.

IP protection was also instrumental in getting the product market-ready. “We started to look for suppliers only after we filed the provisional patent application in Singapore and signed a non-disclosure agreement with the supplier,” says Matt. “Before that, we made iterative prototypes purely in-house.”

There are other ways to protect a product.

To obtain patent protection, you can file an application with individual national and regional patent offices. That incurs fees for each application. At the international level, you can apply for a patent in each country in which you are seeking protection, or use the WIPO PCT System.

Trademark protection also requires registration at the national or regional level. To register a trademark internationally, you can use the WIPO Madrid System or apply in each country where you wish to market your product.

Industrial design protection also requires registration in each jurisdiction. The WIPO Hague System offers international protection for designs.

Matt is considering other forms of IP protection as well, including applying for a trademark for the name “Hanabii” in the childcare products segment.

“Since the Hanabii Pacifier has a unique floral look, we might also consider registering it as a design in Singapore,” says Matt, “but that is a lower priority for now.”

Change the product, change the patent

The functional features of the Hanabii Pacifier have evolved over the past two years and, now that the team is working with a pediatric dentist, they will continue to change. The doctor helped Hanabii to create an orthodontic teat and add holes to the pacifier’s petals to improve ventilation. The pacifier has also been sent to TÜV SÜD Singapore to be tested under US pacifier and toy regulations.

“We believe very much in our product and our market, and think the cost is worth the risk.”

Each change meant that Matt and his lawyers had to amend the patent application. “There are special words and details to pay attention to when drafting patent claims,” says Matt.

He also continues to seek assistance. Initially, the IAP program waived the consultation fees of the patent attorney but not the filing and administrative costs. Still, says Matt, costs have been heavily reduced, particularly during the back-and-forth consultation and redrafting to better protect the IP.

So far, moving from a provisional patent application to the PCT stage has cost Hanabii about US$4,000. “For a small commercial product and at a pre-launch stage, that is no small amount with zero sales coming in,” says Matt. “But we believe very much in our product and our market, and think it is worth the risk.”

WIPO launched the Inventor Assistance Program (IAP) in 2015. It currently counts nine participating countries (Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Kenya, Morocco, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore and South Africa). Marking its 10th anniversary this year, the Program is expanding its services beyond patent drafting and prosecution by offering guidance on commercializing patents. The Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) launched the program in 2023 to help young inventors aged 18 to 35 start their IP journey.