Cecelia Thirlway, redatora freelance

As mudanças climáticas são um dos desafios mais urgentes e complexos do nosso tempo. Para preservar o ecossistema do nosso planeta, devemos reduzir drasticamente as nossas emissões líquidas de dióxido de carbono (CO2), enquanto continuamos a sustentar uma população em expansão.

Que o problema é real e é agora é amplamente incontestável. Mas a maneira como deveremos enfrentá-lo continua a suscitar debates. Alguns acreditam que devemos aprender simplesmente a consumir menos. Outros acreditam que só a inovação tecnológica pode resolver o problema.

Mas será que a capacidade de criatividade e inovação da humanidade pode realmente salvar o mundo?

Melhorar nossa eficiência

O cumprimento das metas de emissões para limitar o aquecimento global a 1,5°C é um desafio significativo e “exigiria transições rápidas e abrangentes nos sistemas energético, terrestre, urbano e de infraestrutura (inclusive transportes e construções), bem como industrial”, segundo um relatório do Comitê Intergovernamental sobre Mudanças Climáticas (IPCC).

A inovação é sempre arriscada, e a complexidade do cenário torna esses mercados difíceis de serem previstos, portanto a propriedade intelectual (PI) permanece sendo um poderoso ativo empresarial quando se trata de enfrentar alguns dos nossos maiores desafios.

Professor Steve Evans, Institute for Manufacturing, Universidade de Cambridge, Reino Unido.

Como consumidores, podemos desempenhar nosso papel na redução da atividade intensiva em carbono: Diminuir nossos termostatos, comprar comida local, fazer viagens aéreas com menor frequência, caminhar e pedalar mais. Mas tais mudanças comportamentais, especialmente em escala global, exigem tempo e dependem de uma complexa interação de fatores.

Nossos próprios esforços podem parecer uma gota no oceano. Até mesmo o consumidor mais bem-intencionado tem dificuldade em fazer as melhores escolhas em um sistema complexo e opaco. Além disso, nem todos os consumidores do mundo podem se dar ao luxo de interrogar sua cadeia pessoal de suprimentos.

Então, como podemos garantir que nossas emissões diminuam, quando nosso consumo continua a aumentar? Seria a inovação a resposta? O Professor Steve Evans, do Instituto de Manufatura da Universidade de Cambridge tem uma visão diferenciada.

“Preocupa-me o fato que estejamos tão desesperados em inventar nossa saída para o problema que acabamos não mudando nossa maneira de encarar o mundo. Vamos apenas voltar nossas esperanças para as energias renováveis, para a captura de carbono, para pessoas em laboratórios que resolvam o problema, em vez de serem dirigentes de empresas, políticos e cidadãos que entrem em ação.”

As provas da engenhosidade humana empregada na luta contra as mudanças climáticas são abundantes.

O trabalho do Professor Evans envolve a identificação de áreas de desperdício para melhorar a eficiência – de recursos, de tempo, de energia e de materiais – nos sistemas de manufatura. Antes de um produto como um carro chegar ao comprador, o processo de produção desse carro já sofreu um impacto ambiental significativo. Suas pesquisas mostram que existe uma ampla margem para a redução desse impacto.

Você sabia?

Cada vez que você lava roupas de lã e outras roupas de tecidos sintéticos, até 700.000 minúsculas microfibras plásticas são liberadas nos rios, nos lagos e nos oceanos do mundo e acabam entrando na cadeia alimentar. A boa notícia é que sistemas de filtragem inovadores podem impedir que isso aconteça.

“Muitos podem pensar, logicamente, que devemos visar a melhor eficiência possível”, diz o Professor Evans. “Lembrem-se que estamos falando de energia, água, materiais e poluição – que custam dinheiro às empresas.” “Economia 101 sugeriria que não estariam fazendo isso com muito desperdício, mas meus dados mostram o contrário.”

incorporado em máquinas de lavar padrão e visa

capturar mais de 99 por cento das microfibras geradas

em uma carga de máquina de lavar roupa.

(Foto: Cortesia do Grupo Xeros Technology)

Ele toma como exemplo o fabricante de automóveis mais eficiente da Europa, que reduziu, nos últimos 14 anos, a energia utilizada para fabricar um carro em 8% a cada ano. Isto significa que agora pode fabricar quatro carros com a energia que utilizava para fabricar apenas um. Com uma economia de custos atingível nessa escala, pode-se esperar que toda a indústria tenha seguido o exemplo, mas, segundo o Professor Evans, isto não aconteceu.

“Se o resto do mercado mudasse na metade do caminho para onde está o melhor agora – apenas na metade do caminho – teríamos 12% a mais de lucros, 15% a mais de empregos e 5% a menos de gases de efeito estufa.”

Assim, devemos procurar reduzir o desperdício e melhorar a eficiência nas fábricas e na indústria, em vez de inventar novas tecnologias para enfrentar a crise climática? Não necessariamente, segundo o Professor Evans: É preciso equilibrar, agilizar e eliminar os riscos incorridos pelo processo de trazer novos conhecimentos ao mercado.

“Temos tecnologia suficiente para sermos sustentáveis hoje – temos de aprender a trazer essas coisas para o funcionamento diário.”

Para tanto, como Presidente do Projeto X Global, um ambicioso acelerador, ele está trabalhando para ajudar os cientistas a comercializarem rapidamente suas invenções.

“Se você for cientista num laboratório universitário de pesquisas [e] se você patentear algo, levará entre 10 e 15 anos para que essa tecnologia se confirme. Interessa-me atingir esse objetivo em 10 a 15 meses.”

O Projeto X concentra seus esforços no enigma da primeira encomenda de envergadura: Os investidores muitas vezes querem que as startups tenham garantido uma encomenda de envergadura antes de se comprometerem, mas a maioria das empresas não vai trabalhar com startups pequenas e de alto risco nessa escala. Isso significa que o crescimento orgânico normalmente acontece em um longo período de tempo. O Projeto X tem como objetivo dar um salto nesse processo.

“Trabalhamos com uma grande empresa para ajudá-la a definir os problemas que tem, e depois buscamos invenções que a ajudem a resolver esses problemas. Mas, o que é mais importante é que antes de fazermos isso a empresa prometa fazer grandes encomendas para qualquer tecnologia que passe no teste que tiver sido definido. Eles ditam os testes, mas se algo passar, eles compram 1.000 toneladas ou 10.000 unidades ou algo assim".

Para reduzir os riscos incorridos pela iniciativa para a empresa, o Projeto X Global emprega uma robusta metodologia de pesquisa, combinada com a revisão por pares, com vista a garantir que apenas as soluções mais eficazes e sustentáveis sejam selecionadas.

A inovação é sempre arriscada, e a complexidade do cenário torna difíceis quaisquer previsões para esses mercados, de maneira que a propriedade intelectual (IP) continua sendo um poderoso ativo empresarial quando se trata de enfrentar alguns dos nossos maiores desafios.

O Grupo Xeros Technology é um excelente exemplo: Suas tecnologias estão ajudando as indústrias de confecção e limpeza a reduzirem o consumo de água e o uso de energia em processos como tingimento ou lavagem. A empresa, que é construída inteiramente sobre IP, licencia suas tecnologias para fabricantes de todo o mundo.

"Nosso modelo de negócio é obter receita de licenças com nosso IP, não participamos diretamente dos mercados", explica Mark Nichols, Presidente Executivo da Xeros. "Portanto, é vital que protejamos nossas patentes e marcas para garantir e proteger nossas receitas e gerar retorno sobre o investimento que fizemos no desenvolvimento de nossas inovações em produtos comerciais. Muito simplesmente, sem patentes robustas e extensa cobertura geográfica, não poderíamos manter nossa empresa".

Como exemplo, as tecnologias XOrbTM da empresa, que são polímeros esferoidais, só precisam de baixos níveis de água e química para remover sujidades e tinturas dispersas na lavagem de tecidos. Também tornam os processos de tingimento de tecidos (por exemplo, penetração e fixação) mais eficientes, reduzindo drasticamente o tempo, a água e a energia necessários.

Com mais de 40 famílias de patentes em uma ampla gama de tecnologias, a Xeros adota uma abordagem focalizada e estratégica à sua PI e atrai investidores que entendem o valor das tecnologias que desenvolve, bem como a necessidade de protegê-las.

"Vemos um número crescente de fundos sendo criados para fazer investimentos ‘verdes’, com a Bolsa de Valores de Londres agora também conferindo uma Marca de Economia Verde para empresas que geram pelo menos 50% de suas receitas com produtos e serviços que contribuem para a economia verde global".

A tecnologia de captação direta de ar constitui boa parte de um portfólio de soluções. Não é de forma alguma uma solução milagrosa: a escala da crise climática é tal que precisamos de todas as soluções trabalhando em conjunto.

Louise Charles, Diretora de Comunicações, Climeworks

Remoção de CO2

A ciência demonstra que, para atingirmos as metas de temperatura definidas, precisamos não apenas reduzir nossas emissões, mas também remover o CO2 existente da atmosfera.

Grande parte da tecnologia de captura e sequestro de carbono já existe há décadas: O problema sempre foi de escala. Veja, por exemplo, o caso da captura direta de ar.

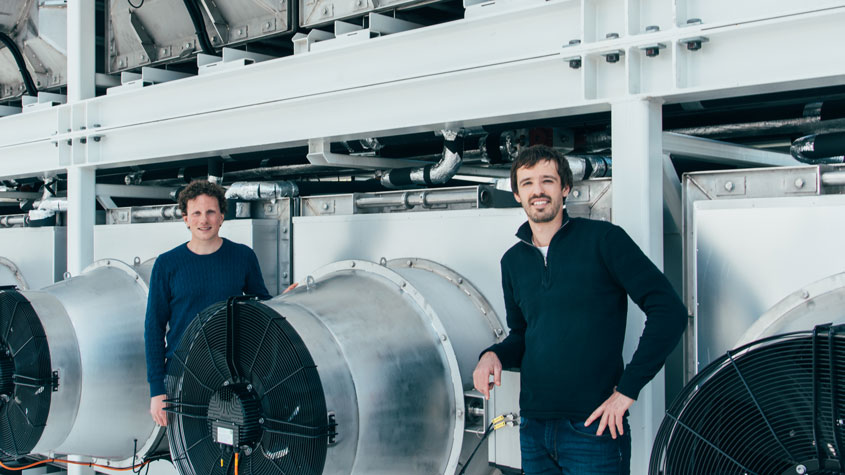

"Capturar CO2 do ar não é nenhuma novidade. Isto tem sido feito em submarinos e em viagens espaciais, em qualquer lugar onde os humanos precisem respirar em um espaço fechado por um período mais longo", explica Louise Charles, Gerente de Comunicação da Climeworks. "O que a Climeworks está fazendo de diferente é capturar CO2 em uma escala muito maior".

Fundada por dois engenheiros mecânicos suíços que estudaram a captação direta de ar na ETH Zurique, a Climeworks desenvolveu unidades de captação direta de ar em larga escala com base em um sistema modular de coletores de CO2. Estes coletores, cada um do tamanho de um pequeno carro, podem ser empilhados em qualquer número de configurações para criar uma unidade de qualquer tamanho que extrai CO2 do ar ambiente. O CO2 pode então ser vendido para a fabricação de bebidas gasosas, combustíveis neutros em carbono ou fertilizantes. O CO2 capturado também pode ser armazenado no subsolo através da injeção de uma mistura de CO2 e água em formações rochosas adequadas, nas quais uma reação química transforma o CO2 em pedra. A única exigência é uma fonte de energia renovável, e se o CO2 for armazenado em vez de vendido, um local geológico adequado para armazená-lo.

Nosso clima é um sistema interligado que depende de uma multiplicidade de fatores. Isso significa que mesmo definir os problemas certos a resolver - o primeiro passo normal para a inovação - é, em muitos aspectos, mais difícil do que chegar a uma solução.

"Atualmente temos emissões cinzas de 10%, então para cada 100kg de CO2 que removemos do ar, ao longo do ciclo de vida daquela unidade, vamos reemitir 10kg". Em outras palavras: temos uma eficiência líquida de 90%, e nossa meta é elevar essa eficiência para 94%. A captação direta de ar não requer muita terra, e o processo não requer água - na verdade, produzimos água como subproduto".

A Climeworks detém várias patentes sobre a sua tecnologia e tem uma opinião positiva sobre o seu valor em termos de proteger o seu conhecimento e ajudar a garantir o investimento. Originalmente financiada através de programas de aceleração e bolsas de pesquisa, a empresa começou a operar em 2009, e até o momento já garantiu 50 milhões de francos suíços em investimentos.

"A tecnologia de captação direta de ar constitui boa parte de um portfólio de soluções. Não é de forma alguma uma solução milagrosa: a escala da crise climática é tal que precisamos de todas as soluções trabalhando em conjunto".

Mas será que existe um mercado robusto para esta tecnologia? A resposta é sim. A indústria de combustíveis renováveis está ganhando impulso e o mercado de remoção voluntária de CO2 (em oposição à compensação necessária para a conformidade) está crescendo rapidamente. O último relatório Forest Trends sobre captura de carbono mostra um aumento de 52% na compensação desde 2016 e sugere que o mercado está se aproximando de seu ponto crítico.

Retorno à natureza

Outras iniciativas para enfrentar as mudanças climáticas, no entanto, não requerem muita invenção. De forma surpreendente, o acima mencionado relatório Forest Trends mostra um aumento de 264% nas compensações geradas pelas atividades florestais e de uso da terra - das quais 57% estão concentradas no Peru. O reflorestamento pode ter um efeito considerável no sequestro de carbono, na biodiversidade e nos ecossistemas em geral.

Em 2000, Isabella Tree e seu marido Charlie Burrell começaram a reconstruir sua propriedade Knepp Estate de 3.500 acres no Reino Unido, permitindo que ela voltasse completamente à natureza. Os resultados foram surpreendentes: Em dois anos, a terra estava repleta de vegetação e de insetos em números não vistos por gerações e agora é um ponto de reprodução para várias espécies de aves criticamente ameaçadas de extinção. Mas, não menos importante é que o valor da Fazenda Knepp como sumidouro de carbono, avaliado para o DEFRA (Departamento de Meio Ambiente, Alimentação e Assuntos Rurais) pela Universidade de Bournemouth, subiu de uma pontuação de 1 para uma pontuação máxima de 5. Segundo o livro sobre Knepp Estate da Sra. Tree, a avaliação estima que, ao longo de 50 anos, ela irá capturar e armazenar um valor adicional de 14 milhões de libras esterlinas de carbono através de seus prados restaurados e florestas de folha larga.

Mas enquanto o IPCC sugere que um aumento de 1 bilhão de hectares de floresta é necessário para ajudar a limitar o aquecimento global a 1,5°C até 2050, o mapeamento recente da cobertura florestal da Terra revela que pode haver apenas 0,9 bilhão de hectares disponíveis para reflorestamento, sem interromper o uso humano atual. A escala de tempo também é um desafio:

“A captura de carbono associada à restauração global não poderia ser instantânea, pois seriam necessárias várias décadas para que as florestas atingissem a maturidade.”

As provas de engenhosidade humana empregada na luta contra as mudanças climáticas são abundantes. A Project Drawdown, uma organização de pesquisa que revisa, analisa e identifica as soluções climáticas globais mais viáveis, relaciona mais de 80 categorias de soluções que vão desde a redução do desperdício de alimentos e planejamento familiar até micro-redes e bioplásticos inovadores.

Mas enfrentar um problema tão complexo não é fácil. Nosso clima é um sistema interconectado que depende de uma multiplicidade de fatores. Isso significa que mesmo definir os problemas certos para resolver - o primeiro passo normal para a inovação - é, em muitos aspectos, mais difícil do que chegar a uma solução.

O que é certo na corrida para salvar nosso precioso planeta é que novos conhecimentos e know-how estão sendo criados a um ritmo sem precedentes. Nosso sucesso na superação deste desafio assustador provavelmente dependerá de uma combinação de inovações inspiradas, mudanças profundas nos hábitos de vida e uma atitude mais responsável em relação à biodiversidade e aos sistemas naturais deste planeta. Como disse recentemente David Attenborough a um menino de cinco anos de idade que lhe havia perguntado o que ele poderia fazer para salvar o planeta:

Não desperdice energia elétrica, não desperdice papel, não desperdice comida. Viva do jeito que você quer viver, mas não desperdice. Cuide do mundo natural, e dos animais nele, e das plantas nele também. Este é o planeta deles, assim como o nosso. Não os desperdice". Este é o planeta deles, assim como o nosso. Não os desperdice.