By Catherine Jewell, Information and Digital Outreach Division, WIPO

Graphenel JSC, based in Ho Chi Minh City, is a technology company that specializes in the large-scale production of graphene and its applications. Jane Phung, responsible for the company’s international business development, discusses the company’s novel approach to graphene production, the challenges it faces in Viet Nam’s nascent graphene market and the role that intellectual property (IP) plays in supporting its ambition to become a leading industrial supplier of graphene-based materials.

What are the origins of the company?

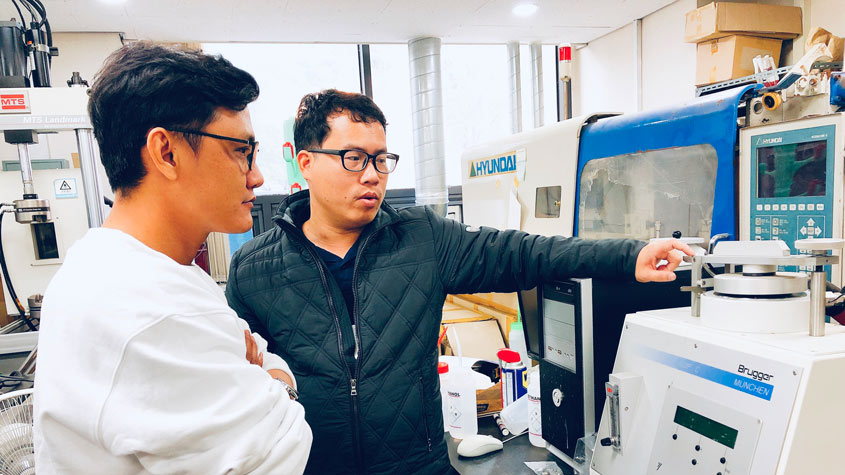

The company was set up by Tuan Le, our CEO, and Jat Le, our Chief Project Officer, in 2011. They studied together, majoring in chemistry and nanomaterials. After graduation, they started a business, NanoLife, which focused broadly on nanomaterials. Then, when graphene and its amazing properties came into focus, they began working exclusively on it and re-branded the company as Graphenel JSC.

At the time, graphene was scarce, and its manufacture was costly. So, my colleagues decided to find a more cost-effective way to develop graphene. After around seven years of research and a lot of trial and error, they came up with a novel process for manufacturing graphene. In broad terms, we refine animal fat − such as that used to produce cosmetics − to mass produce graphene in a cost-effective way. In general, it takes around 1 kg of refined animal fat to create 1 gram of graphene, and a single production cycle, which produces 6 kilograms of graphene, takes around two days.

Tell us more about your business model.

Unlike other countries with established graphene markets, few people in Viet Nam are familiar with graphene and its amazing properties. So, to develop our business, we have been relying on our networks to help spread the word in the market about what we are doing. We sell our graphene products to researchers working on new materials. They have been very helpful in referring us on to other companies they work with. This has allowed us to promote broader understanding of the value that our materials can add and to expand our client list.

We also recently launched a new cooperation program, where we co-develop new materials and products using graphene with universities, research institutes and small companies. Program partners agree to use our graphene products as input materials. It’s a win-win situation; they benefit from our products and expertise to advance their research, and we create an opportunity to commercialize any marketable outputs that flow from the research project. We anticipate the program will accelerate the product development process and our journey to market.

So far, we have agreements in place with two universities and one private company.

A number of products are in the pipeline, which we hope to introduce to the market by the end of 2022.

Is there a big demand for graphene in Viet Nam?

In global terms, it’s not so big, but there is certainly enough demand for us to generate revenue. Of course, going forward, our aim is to increase our market share at home and in Australia and France, where we have clients, as well as in other export markets.

With graphene, it will be possible to improve the carbon footprint of the building and construction sector – cement production currently accounts for around 6 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions – and open the way for greener approaches to building and infrastructure design.

What types of graphene applications are you focusing on?

For now, our top priority is the work we are doing with Ton Duc Thang University on the use of graphene admixtures in cement production to increase the strength and longevity of buildings. Tests show that the compressive strength and the tensile strength of cement can increase by up to 40 percent and up to 30 percent, respectively. With graphene, it will be possible to improve the carbon footprint of the building and construction sector – cement production currently accounts for around 6 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions – and open the way for greener approaches to building and infrastructure design.

We are also working on two other projects. The first is with an American-Vietnamese business to integrate graphene into wearable medical devices to monitor the health of the person wearing it. Graphene is a highly conductive material and when embedded in other materials can conduct electric signals and act as a powerful sensor with a wide range of applications, including in bioelectronics. In general, graphene makes composite materials smart.

The other project is with Jeonbuk National University in the Republic of Korea, where we are working with researchers to find ways to improve the lifecycle and durability of batteries using graphene.

What has been the response from Vietnamese businesses?

We have been talking to big companies in Viet Nam and they are very excited about our research and what can be achieved with graphene. There is, however, a general concern about the cost implications of using it in their products. They also stress their need for a stable and reliable source of graphene that is capable of meeting their industrial-scale needs. If we can meet that demand, the prospects are promising. That’s why we are scaling up our production capacity.

What role does intellectual property play in the company?

Intellectual property is super important to us and has been pivotal in enabling us to secure funding. As graphene was so new in our market, the only way to attract the funds we needed was to demonstrate the validity of our manufacturing process to investors. On the strength of the patent application that we had filed with the Intellectual Property Office of Viet Nam, we were able to do this. With that application, and the strong profile and experience of our co-founders, our investors began to trust our process.

When we saw that our innovation had value, we realized we needed to protect it immediately. Although the graphene market in Viet Nam is not well developed, many companies around the world make graphene, so it was clear that only by protecting our IP could we remain competitive.

We filed our application in September 2019. It is still in process, but we hope to receive confirmation that the patent has been granted by the end of 2021.

Why is it important for Graphenel to collaborate with university researchers?

Simply because university researchers are able to spread knowledge about this material to their students, who in turn, apply it to different products. University researchers understand the importance of graphene and the value it adds to products. Through their peer-reviewed articles and contacts, they will transfer knowledge about graphene and its potential applications to their peers in Viet Nam and elsewhere. In this way, people will learn about graphene and our products.

How do you protect your IP when collaborating with universities?

Through a combination of non-disclosure agreements and other agreements in which our partners agree not to reveal details of our manufacturing process. In general, when we engage with them, we give a general overview of our process, without disclosing core details; they know what is going on but not enough to copy it.

Graphene covers a family of materials, each with different properties. What types of materials do you produce?

We produce graphene in its rawest form. We have four featured products: graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide, graphene layers and graphene nano-platelets. They are all powder products and while they can be used for the same purposes, some forms are more suitable for specific products.

For example, our graphene nano-platelets are best suited to cement admixtures and some water treatment products, whereas graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide are more suited for use in sensors and batteries. We sell our graphene layers to companies who process the graphene themselves without our help.

When we saw that our innovation had value, we realized we needed to protect it immediately.

How much graphene do you produce every year?

Right now, we produce around 100 kg of graphene layers, 1 tonne of graphene nano-platelets and 10 kg of graphene oxide. But we are in an expansion phase. We currently have five full-time staff and a growing number of part-time staff who work in our factory. By year-end, we expect to increase our production capacity 10-fold.

What are the main challenges you are facing?

As I mentioned before, building awareness about graphene and its properties has been a big challenge. Then, in entering foreign markets, we confronted low levels of trust among prospective clients. Our approach to IP was an important factor in dispelling their doubts about us, and actually opened conversations with a number of companies from other countries. It encouraged them to look at our process more closely and when they did, they found it was more interesting than they first thought.

Cost also remains an issue. While the cost of graphene has dropped significantly over the last decade, it’s still expensive for companies to use on a large scale. So, we need to find ways to further reduce its cost. We also need to continue working with prospective clients to demonstrate the potential benefits of using graphene in their products.

Quality control is another important issue. Viet Nam doesn’t yet have a quality standards authority for graphene. We have been trying to overcome this by benchmarking our graphene products against those from other countries. When looking at new markets, we also look at their standards. For the moment, we simply work to ensure that our materials do what we say they do. It is rather difficult to talk to people about quality when we don’t have any national standards in place. So, we would like to see the development and implementation of quality standards for graphene that other industries can understand and trust. Only then will customers have confidence in the quality of our products. We are working with the national authorities on this. I think we are on the right track, but we need to be faster if we want to make inroads to the market.

About graphene

In 2004, researchers at the University of Manchester in the UK, Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov, first isolated graphene. They used sticky tape to separate graphite into individual layers of carbon. Their work won them the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2010.

Hailed as a “wonder material,” graphene is a one-atom-thick layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, with a number of interesting properties. “It's the thinnest possible material you can imagine. It also has the largest surface-to-weight ratio: with one gram of graphene you can cover several football pitches […] It's also the strongest material ever measured,” noted Andre Geim in an interview with Nature in October 2010.

Graphene is around 200 times stronger than steel and is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity with “interesting light absorption abilities.” It can be combined with other elements to produce different materials with enhanced properties for a variety of uses, from construction to medical sensors to batteries.

According to Graphene-info, graphene is “truly a material that could change the world, with unlimited potential for integration in almost any industry.”

What needs to be done to support the commercialization of graphene materials and why is this an important issue for policymakers?

Policymakers have an extremely important role to play in developing a policy environment for the graphene market to thrive. This involves establishing quality standards for the manufacture of graphene that the market can trust. It also means clarifying the legal boundaries governing the commercialization of graphene.

We would like to see policies, such as tax breaks, to support domestic production of graphene for both home and export markets. Such policies would enable domestic graphene producers to compete with producers from other countries. If the government could do something support local graphene production, it would be good.

Intellectual property is super important to us and has been pivotal in enabling us to secure funding.

Has graphene and its potential been overhyped?

No, not really. It’s true, it has applications in many sectors, but so do other materials. The problem is, we don’t yet fully understand how it can be best applied. I think graphene has a good future, but is it forever? I’m not sure. It’s highly likely that some other amazing new material will come along to compete with it in the future.

What new uses of graphene materials are you most excited about?

Personally, I am most excited about electrical batteries. Right now, a lot of our devices rely on batteries, so if we could use graphene to improve the lifecycle of batteries so they charge more quickly and hold more power for longer, it would be amazing. It would mean we could cut the number of batteries we throw away every year and help make the world greener.

What are your plans for the future?

We will continue to develop our work in the areas of bioelectronics, cement and batteries. We are particularly excited about the battery industry and are keen to educate that market about graphene and to develop and commercialize good graphene-based batteries for a greener society.