By Peter Jaszi, Professor of Law Emeritus, American University Law School, Washington, D.C.

Experts have been discussing whether and how to protect traditional cultural expressions, or the “old arts”, since the 1950s. But the work of WIPO’s Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore is fueling renewed scrutiny of the topic.

As international lawmakers grapple with the choices involved in shaping any new international legal regime to protect traditional cultural expressions, it is timely to carefully consider the “gaps” in the law that may – or may not – need to be addressed, and to reflect on whether existing international copyright laws can support, albeit partially, recognition of traditional cultural expressions.

Before going further, there are two points to bear in mind. The first is that not every identifiable gap in the law needs to be filled. As an example, 19th-century champions of expansive copyright believed that term limitations were a defect in the system that would be remedied by introducing a principle of perpetual protection. Since then, however, Western copyright experts have generally embraced the value of term limits (albeit very generous ones) as a way of assuring a public domain and maintaining balance in the system.

Second, only a multilateral solution can adequately address the specific problems facing the protection of traditional cultural expressions, many of which occur in the global information economy. International IP law assures recognition of rights across the national boundaries of states that sign up to it. It also assures some degree of harmonization among national laws by establishing mandatory minimum standards for national legislation.

Spotting the gaps

The absence of an international agreement on the protection of traditional cultural expressions is a major structural gap in international law. Some commentators attribute this to the fact that existing IP laws have been constructed around a paradigm that is selectively blind to the scientific and artistic contributions of many of the world’s cultures and established in forums where those most directly affected are not represented. They argue that systematically treating the cultural productions of some communities as naturally occurring raw materials for use by others risks putting a brake on human progress.

There are also gaps at a more functional level, in that there are some things the law does not accomplish – and arguably should. The difficulty in addressing these gaps was driven home to me some years ago on a field trip in Samosir Island in North Sumatra, Indonesia. Together with my fellow researchers, I was invited by chance to a traditional funeral celebrating the life of a local matriarch. It was a joyous event involving dancing couples and a group of young local musicians performing traditional music on local string and drum instruments and an electronic keyboard. The keyboard player told us he loved the old music, but enjoyed tweaking it to reflect Western popular musical influences. He also revealed that the prohibitive cost of hiring a large group of musicians with traditional instruments made using the electronic keyboard an economic necessity. Through this kind of hybridization (and streamlining), he explained, the old music continued to live in the community.

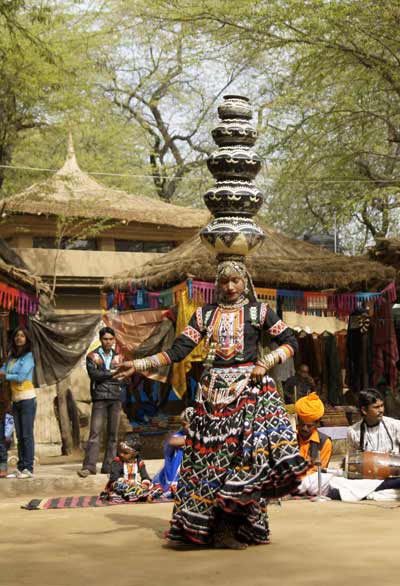

traditional cultural expressions is a major structural gap in international

law (photo: Jeremy Richards / Alamy Stock Photo).

That conversation took us back to a formal interview we had conducted earlier with community leaders elsewhere on the island who had expressed concern about the “misuse” of the musical tradition through the inclusion of Western instruments in local ensembles. Some villages had even banned such performances, and others only stopped short because there was no clear legal basis for doing so.

These diverging perspectives prompted us to question whether the lack of a legal mechanism to regulate the way traditional cultural expressions are transmitted across generations is actually a flaw. Should communities’ freedom of choice about how to adapt old cultural practices to new circumstances be preserved instead? This is a hard, value-laden choice and underlines the fact that not all gaps need filling.

Reaching conclusions about what to leave unregulated often reveals the most profound differences in values and aspirations. Nonetheless, there is a broad perception that gaps exist in at least three functional areas: attribution, control and remuneration.

When it comes to attribution, the people associated with traditional cultural expressions, including the states in which they reside, aspire to legal guarantees that when traditional cultural expressions are disseminated, their sources are fully and appropriately acknowledged. At present, no such assurances exist for traditional cultural expressions as a whole.

Similarly, there are concerns about the need to control the use of traditional cultural, especially those regarded as “secret”, or intended by custom to circulate only within limited groups.

And with respect to remuneration, there is today a widely shared view that traditional cultural expressions are often exploited far from their places of origin, and that a fair international regime would include a mechanism to prevent (or redress) such “misappropriation”.

Are existing IP regimes part of the solution?

While any new proposal will certainly be judged by how successfully these functional gaps are addressed, the discourse around the protection of traditional cultural expressions tends to concentrate on whether existing regimes of protection adequately cover the specific provisions required to meet the aspirations of indigenous groups.

From this viewpoint, how far are existing copyright laws part of the solution? Can the problem be solved by simply tweaking the Berne Convention to bring traditional cultural expressions within the scope of international copyright law? Back in 1971, lawmakers sought to do this by introducing Article 15.4 into the Berne Convention. The article outlines arrangements for certain unpublished works of unknown authorship (see box), but because it is optional little has changed. Most countries have not enacted it. Moreover, protection for such works is limited to at least 50 years, and only once the work is “lawfully made available to the public.” It also makes no explicit mention of the role of communities: rights on behalf of the author are exercised by “a competent authority.” Its scope is further limited by Article 7.3 of the Convention, under which countries are not required to protect anonymous works when it is reasonable to presume the author has been dead for 50 years.

But is there a case for simply repairing these defects? After all, bringing traditional cultural expressions into the fold of copyright law would offer remedies to address misuse of traditional cultural expressions, including injunctive relief and damages in most countries. It would also trigger the mandatory application of basic moral and economic rights in at least 170 countries.

What copyright law does and does not do

On the downside, such an approach fails to effectively protect traditional cultural expressions on a number of counts.

Copyright has evolved around the idea of “authorship” to favor claims of rights in ascertainably original and relatively recent products of imagination. Over time, copyright law has been remarkably flexible in defining “authorship”. For example, an object qualifying for protection may originate from an individual (e.g., a novel) or a group (e.g., a film). Common law jurisdictions have even fictionalized the idea by introducing the “work for hire” doctrine, whereby an employer is considered the author of the merged contributions of employees. But there are limits – and instances beyond the ingenuity of copyright lawyers – in which not even a fictional person can comfortably be assigned responsibility for a cultural tradition, the value of which has been produced collectively (rather than collaboratively) by a group.

Moreover, traditional cultural expressions have often been understood as lacking individualization, originality, recentness and fixity. Many individual traditional cultural expressions may satisfy some or all of these requirements, but others do not. Take, for example, a 300-year-old musical tradition originating from a specific community that continues to practice it today. Let’s assume it consists of a group of simple melodies played on specific instruments with a body of stylistic rules governing how it should be performed. Such a cultural tradition fails comprehensively to fit the grid of copyright. It lacks even hypothetical individual “authors”; it is not “original”, having been faithfully transmitted across generations; and it lacks the required definite form – unless a work has a stable form capable of more or less identical repetition, it is not copyrightable.

Is partial protection of TCEs possible under copyright law?

From the above, it is clear that any attempt to shoehorn traditional cultural expressions into copyright law is simply a non-starter. But is there potential for partial protection of traditional cultural expressions under copyright law?

In relation to concerns about the unauthorized recording and exploitation of traditional cultural performances, a legal regime for the protection of musical performers is already in place in most countries, albeit originally conceived with the commercial music and broadcasting industries in mind. Nothing would seem to prevent these laws being used to protect traditional cultural expressions.

Article 15.4 of the Berne Convention

Article 15.4 of the Berne Convention states that:

“(a) In the case of unpublished works where the identity of the author is unknown, but where there is every ground to presume that he is a national of a country of the Union, it shall be a matter for legislation in that country to designate the competent authority which shall represent the author and shall be entitled to protect and enforce his rights in the countries of the Union.

(b) Countries of the Union which make such designation under the terms of this provision shall notify the Director General by means of a written declaration giving full information concerning the authority thus designated. The Director General shall at once communicate this declaration to all other countries of the Union.”

Today, the traditional cultural expressions most at risk are contemporary variants of ancient musical, choreographic, graphic and other traditions. These works are likely to be the most attractive and accessible to would-be exploiters. Contemporary copyright law actively protects new versions of preexisting works – the modern retelling of a Greek myth, for example – as a “derivative work”. The resulting protection is more than sufficient to tackle most cases of piracy, and in most jurisdictions the individual interpreter’s moral right of attribution is protected.

But while a contemporary variant of a cultural tradition fits comfortably within the grid of copyright law, traditional cultural expressions as a whole do not, and in various ways. First, copyright law fails to protect secret or sacred knowledge, which typically maintains its original form across generations. Second, it does not protect the attribution interests of the communities that give rise to contemporary interpretations of traditional cultural expressions. Third, the protection afforded to contemporary variants of traditional cultural expressions is limited in scope: it is applicable to reproductions, performances and displays of relatively close imitations, but not to all new work “inspired” or “influenced” by them. Fourth, as with all copyrightable subject matter, variants of contemporary traditional cultural expressions would ultimately enter the public domain. And perhaps most significantly, the rights conferred by copyright are subject to statutory exceptions (e.g., for education, museums and archives), the scope of which varies – sometimes significantly – from country to country.

Questions for lawmakers

Should lawmakers consider leaving some gaps unfilled when designing a new legal regime to protect traditional cultural expressions? Might this support the communities that sustain traditional cultural expressions? And can they learn from the values expressed in copyright law?

Take, for example, term limitations and the concept of a public domain. Are these ideas simply an unwanted intellectual legacy, or do they have universal appeal? While not an easy question, there is something to be said for “sunsetting” the legal protection of all knowledge. One argument for allowing protected traditional cultural expressions to enter the public domain is that – as is the case for moral rights in protected works in many countries – attribution rights in traditional cultural expressions could be made effectively perpetual. This question deserves additional, clear-eyed consideration. Similarly, might traditional cultural expressions qualify as one of the protected and affirmative carve-outs for certain privileged uses that feature in all existing IP systems?

One further point of fundamental inquiry relates to the familiar pronouncements about how IP should serve the spread of knowledge among all peoples. Are these simply fig leaves for injustice, or are they valid despite the self-serving ways they often are deployed? And if they are valid, can they be accommodated through a model of protection based on concepts of compensation rather than exclusivity?

These are some of the unavoidable questions that lawmakers will need to address when deciding how porous or “gappy” a system of protections for traditional cultural expressions should be.