IP value capture: fostering trade by capturing the value of creative industries in developing countries

By Keith Nurse, Senior Fellow, Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, World Trade Organization Chair, University of the West Indies, Barbados

In today’s digitally-driven global knowledge economy, IP value capture – the commercialization of intellectual property (IP) assets – offers developing countries significant growth opportunities. Adding value through the use of IP helps these economies expand their participation in global value chains and reduces their dependence on traditional low value-added commodity agriculture, mineral, and services exports.

Given the potential of IP rights to promote economic diversification, and the limited industrial capacity of small and least developed countries, IP value capture within the creative industries should be a key consideration when crafting development and trade policy. But finding ways to enable developing countries and their micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to participate in this growth is a key challenge. It involves developing a better understanding of the role that IP rights play in global value chains and how their value can be captured within the creative industries. IP policy also needs to move beyond compliance with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) and isolated attempts to protect and enforce IP rights.

IP value capture is particularly important for MSMEs. These are often the first movers in innovation and IP creation, but their ability to expand is often hampered by market access and trade financing challenges. The fact that many developing countries do not have in place either a strategic industrial development agenda or a framework to foster innovative IP-rich industries and entrepreneurs, compounds these challenges.

IP value and the creative sector

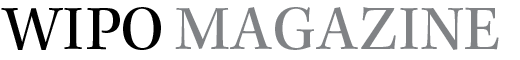

Investment in the IP value embedded in the creative industries presents a number of opportunities. In particular, in terms of copyright and related rights income, for example, from the exploitation of authors’ neighboring and synchronization rights. IP value capture in the creative sector does not stop there. Used strategically, IP rights can generate economic value in sectors like tourism (through destination and nation branding), manufacturing (through the use of geographical indications, appellations of origin, and own-brand manufacturing), and information and communication technologies (ICTs) (through ecommerce, media value, and data monetization). IP assets can also be used as collateral or security to finance the development of creative industries (see Figure 1 below).

Since the global economic crisis, the creative sector has outperformed most other sectors of the global economy. In part, this is due to the growth of the digital economy, where IP and trade in services have expanded as a share of global value-added.

tourist arrivals and generates an equivalent proportion of tourist

spending. It has also been instrumental in fostering the country’s creative

sector as well as its music and masquerade design exports

(photo: John de la Bastide / Alamy Stock Photo).

From a global value chain perspective the creative industries in many developing countries operate within a highly fragmented and competitive ecosystem, featuring many independent but disconnected creators. Very few large firms or foreign operators participate as primary investors in the production end of the value chain. Larger foreign firms, and those operating in the diaspora, typically act as secondary investors in the more lucrative elements of the value chain, such as manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and copyright administration. As such, the creative sector tends to be poorly served when it comes to access to finance and trade facilitation. These important factors need to be addressed to enable businesses to develop and tap into export markets (See Study on Alternative and Innovative Financing for ACP Cultural Industries, Keith Nurse (2016)).

However, creative businesses can overcome some of these challenges associated with access to finance by using their IP assets as collateral (see Using Intellectual Property Rights as Loan Collateral in Indonesia, Selvie Sinaga (2017)). Music asset-backed securitization, for example, can be facilitated through the appropriate valuation of the catalogue of an artist or a copyright holder. Various famous artists, including David Bowie, James Brown, the Isley Brothers, and Marvin Gaye, have done so with some success.

Royalties from a music catalogue can be substantial. The estate of Reggae icon Bob Marley, for example, is one of the top earning estates from a developing country. In 2017, that estate generated USD 23 million from music royalties, licensing, and branding deals according to Forbes Magazine, making Marley one of the highest earning dead celebrities in the world.

Various financial institutions are looking into IP asset-backed securitization, but the prospects of it becoming widespread in developing countries are limited by a general lack of IP awareness within the investment community of these countries. Moreover, the financial markets in developing countries generally lack effective IP valuation mechanisms or regulatory frameworks to govern creditors’ rights. This area of financing is still considered high risk and remains underdeveloped in terms of earnings. At present, the share of global income from royalties enjoyed by developing countries remains relatively small.

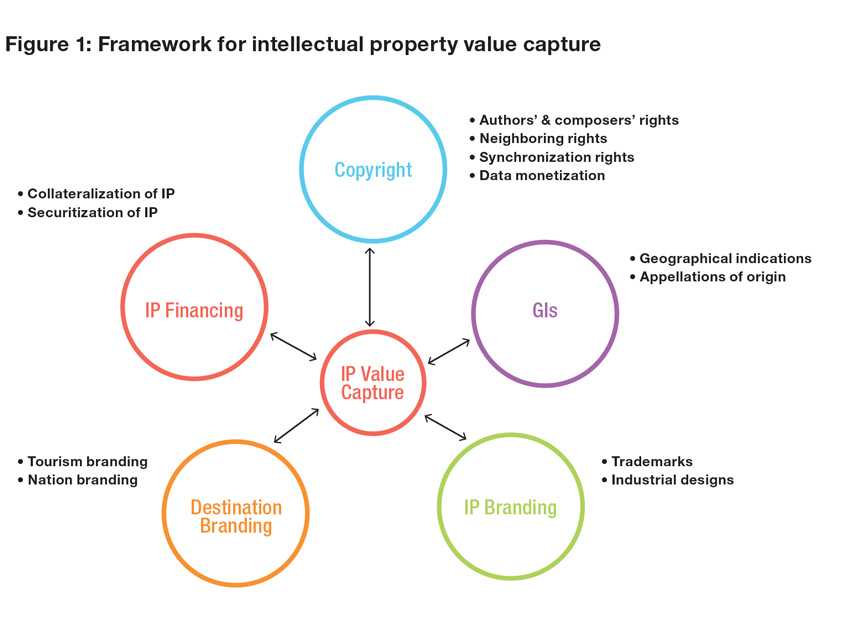

The largest share of global royalties income from the creative industries is generated in Europe (57 percent) and North America (21 percent), compared to the smaller shares in Asia/Pacific (15 percent), Latin America (6 percent), and Africa (1 percent), (see Figure 2 below). Global royalty collections rose from USD 7.7 billion in 2012 to USD 9.2 billion in 2016. The music industry collected 87 percent of that total. Although royalties from digital sources only account for around 10 percent of total global royalty collections, they are the fastest rising component with 50 percent growth in 2017.

Leveraging IP value capture

These upward trends in copyright royalties point to significant potential for IP value capture, in particular by creative industries in developing countries. However, IP value capture in the creative industries is not restricted to direct earnings from assets, such as the catalogues of authors or composers. Right holders can also leverage their IP assets to generate income from merchandizing, franchising, endorsement deals, and events management (e.g. festivals and concerts). The value captured in this way relies less on traditional brick and mortar assets. As such, it is therefore a relatively more accessible business option for small companies, especially those that have built up a strong brand identity in key target markets.

The governments of developing countries can also promote destination branding and tourism using the IP assets of their creative industries. IP assets can be used to promote top-tier events, such as music festivals and carnivals. In this way, they can support “nation branding” efforts to ensure the country stands out as a destination of choice. Trinidad and Tobago has done this with some success. The annual Trinidad and Tobago Carnival, for example, attracts around 12 to 15 percent of tourist arrivals and generates an equivalent proportion of tourist spending annually. The Carnival has also been instrumental in fostering the country’s creative sector and music and masquerade design exports (see The Creative Economy and Creative Entrepreneurship in the Caribbean, Keith Nurse (2016)). For many developing countries, especially small island states, tourism is an important source of employment and export revenues. For these countries in particular, implementation of a cross-sectoral strategy that engages the creative industries offers improved growth possibilities and increased opportunities for value addition.

Another area where there is tremendous scope for value addition is in the use of geographical indications (GIs). Products with characteristics that are rooted in a specific geography or culture may qualify for protection as a GI. Indonesia, for example, has protected its traditional fabric, Batik, as a GI. Indeed, Batik gained global recognition in 2009, when UNESCO recognized it as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (see The Protection of "Batik" Craft under Geographic Indication: The Strategy for Developing Creative Industry in Indonesia, Mas Rahmah (2017)). Against this backdrop Batik exports grew from USD 22 million in 2010 to USD 340 million in 2014 and continue to expand.

Moving up the value chain: key imperatives

Creative industries in developing countries face numerous other barriers to local and global market participation. These include a lack of production facilities, poor market organization, inadequate rules and regulations, limited understanding of global markets, language barriers, poor bargaining power, and limited commercial relationships. Take, for example, the burgeoning audiovisual sector in Africa, where the majority of filmmakers and producers operate micro or informal enterprises. The problems confronting these filmmakers are further magnified by the absence of distribution and marketing networks, making it difficult for them to enter and compete in the global audiovisual markets (see Creative/Cultural industries financing in Africa: A Tanzanian film value chain study, Martin R. Mhando, Laurian Kipeja (2010)).

Enhanced integration of the creative industries of developing countries in global value chains therefore requires a shift in mindset and business practice. Businesses need to place greater emphasis on collaboration and support efforts to foster better coordination and organization within the sector; for example, through the establishment of national and regional industry or trade associations. Value chain integration also requires the development of digital entrepreneurship through tactics such as aggregation of creative content for digital platforms like Amazon, YouTube, Google, Spotify, Netflix, Tencent, or competing firms from the South. Only then will they be able to take full advantage of the opportunities arising from the expansion of digital trade and the proliferation of online streaming and subscription services.

Governments can support the development of their creative industries by establishing an institutional framework (i.e. legislation and incentives) that facilitates the sector’s development and expansion. In so doing, it is important to promote cross-sectoral linkages; only then will it be possible to harness the multiple markets and sources of income generated by creatives industries, many of which intersect with ICTs, manufacturing and tourism.

If developing countries are to take full advantage of the potential that the digital knowledge economy offers local creative industries, governments need to foster initiatives to support IP value capture supported by an expansive range of trade and industrial policies. This requires the design and implementation of a strategic and holistic export-oriented policy framework.

The key challenges here, however, lie in the fact that many existing institutions that support the creative sector operate in silos and are often decoupled from initiatives to enter wider markets. Often, ministries of culture and trade promotion agencies are not working in tandem and, in many cases, Aid for Trade mechanisms only focus on one component of the process, such as training.

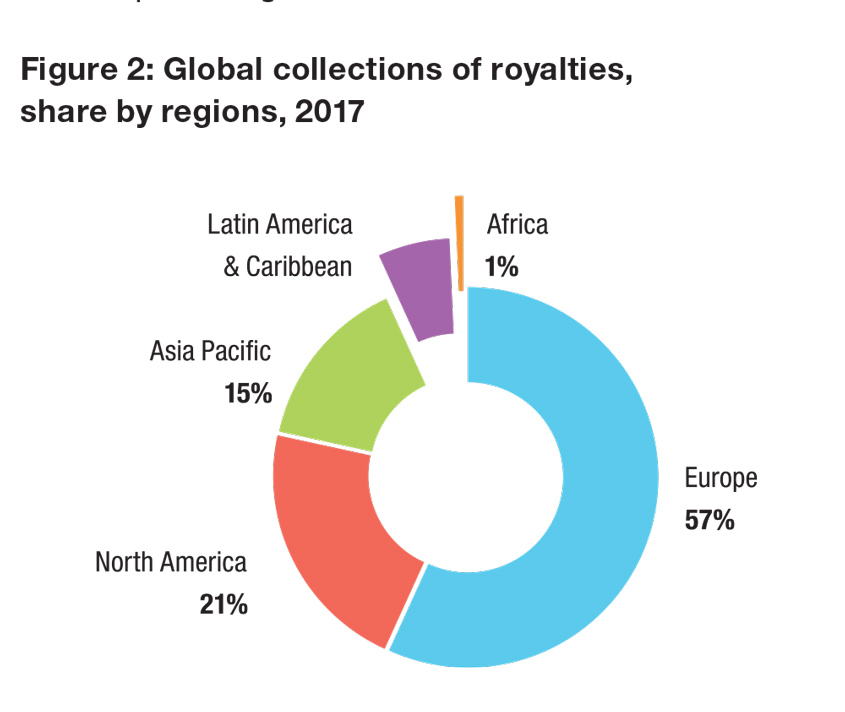

From this standpoint, the provision of end-to-end business solutions and trade and financing support mechanisms would go a long way toward improving the export competitiveness of the sector. Implementing this approach would involve the development of start-ups hubs or camps, sector clusters, and incubators or accelerators for innovation-driven enterprises that are directly linked to market entry programs and new financing mechanisms such as crowdfunding, angel investing and venture capital, along with traditional debt and equity financing. Such measures need to be backed up by an array of strategic policy support measures, which could include diaspora engagement, destination branding, trade and export facilitation, investment policy and human resource development (see Figure 3).

The objective is to make creative entrepreneurs and their work more visible and accessible to wider markets, potential clients, sponsors, investors and policymakers.

In particular, these mechanisms promote youth entrepreneurship through additional facilities like networking, mentorship, and peer-to-peer-coaching. Consequently, business and trade support organizations play a critical role in minimizing the risks associated with the creative sector by offering market development grants, export assistance grants, trade fair access and business competitions.

The WIPO Magazine is intended to help broaden public understanding of intellectual property and of WIPO’s work, and is not an official document of WIPO. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WIPO concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication is not intended to reflect the views of the Member States or the WIPO Secretariat. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WIPO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.